RATHER LIKE RAVENNA

Of a sudden, my historical wargaming interest shifted to the early sixteenth century, specifically, to the series of conflicts known as or referred to as the Italian Wars. [1] Checking the Index copy of Miniature Wargames magazine, I dug out Number 82, the March 1990 issue, from my stored-in-plastic bins collection. [2]

As it had been a fair stretch of time since I last thumbed through the pages of this specific issue, it might be remarked that I read instead of re-read Donnie McArdle’s article “The Italian Wars 1494-1559.” [3] The gentleman offers a brief introduction to the period, discusses his collection of figures (numbers, scale, manufacturers, and paints used), and then lists a few sources, one of these being the work of Sir Charles Oman. The lion’s share of the submission is divided between a look at three battles from this period. Like a wargamer Goldilocks, I was tempted by and “tried” each one. I considered the two-day engagement of Marignano (13 September 1515) and then marveled at the tenacity or was it idiotic bravery of the Swiss at the 27 April 1522 Battle of Bicocca. (I briefly studied the provided diagram of this engagement.) Going back a decade, the 11 April 1512 Battle of Ravenna was the third and last engagement summarized by Monsieur McArdle. (He included a map which was wargamer-friendly to a degree, but unfortunately, there was no compass rose or scale included.) As it turned out, like the better known Goldilocks, this third “chair” or “bowl of porridge” was the engagement that I selected to stage on my tabletop. [4] As the title of this post informs, my effort would not be a true Featherstone effort, but it would bear a passing resemblance to the historical engagement. [5]

Constructing the Terrain

Initially, I thought I would take an even simpler approach and declare the one long-edge of my tabletop represented the Spanish bank of the Ronco. Then, figuring that a little color and some suitable construction paper would not hurt, I thought I would prepare a representation of this position-defining river using functional and inexpensive material. Then, I figured that I could just use stuff I had on hand and so, the thicker blue yarn was secured from a “bits and pieces” bin and an “impression” of the Ronco was quickly “constructed.” I included the road behind the Spanish fortified encampment as well. In addition to the breastworks and other defenses (very basic delineations, to be sure), on the French far left flank, I placed a few patches of marshy ground to depict the soggy and perhaps rough terrain formed by the end of the Fossato Grande and possible flooding of the Ronco. (These patches were fashioned from specialty paper purchased at a local arts & crafts store.) The vast majority of my tabletop was free of terrain features. This may sound strange, given my preferred “approach,” but I normally don’t like a plain-looking battlefield. However, I figured that the various formations and units (i.e., counters) would add sufficient color to please this set of aging eyes at least. There was another positive as well: the opposing armies of French and Spanish would have a relatively “clean surface” on which to work. Then again, there was the “elephant in the room” . . . the Spanish fortifications. Map A gives the reader an idea (hopefully) of what my finished if atypical and comparatively to say nothing of subjectively unaesthetic tabletop looked like.

Drafting and Deploying the Armies

I pulled from the Spanish and Later Spanish, the French and Later French army lists provided on pages 19 and 20 of the Advanced ARMATI booklet. While I did want to have artillery and units armed with the arquebus present on my “model” battlefield, I decided not to field any units of Reiters (i.e., cavalry units armed with swords and pistols).

In terms of the of order of fabrication, the Spanish were prepared first and then positioned to make sure that I had sufficient numbers (but not too many) of infantry, cavalry, and artillery units. Once this was done, I figured out the heavy and light control ratings as well as the army break point. When the Spanish were situated, I turned my attention and energies to building the French and their allies.

In greater detail, the Spanish deployment was as follows.

On the right wing, outside of the line of breastworks, there were:

1 unit of Spanish Knights

2 units of Spanish Heavy Cavalry

2 units of Spanish Light Cavalry (Jinetes)

This command was led by a sub-general.

The right side or branch of the barricade was defended by:

1 unit of Sword & Buckler troops (on the right-most side)

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Sword & Buckler troops (on left-most side of this section of the line)

These formations were commanded by a sub-general.

The long, center segment of the breastworks and defenses was garrisoned by:

1 unit of Light Artillery

1 unit of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Skirmishers (Crossbows)

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

1 unit of Sword & Buckler troops

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Skirmishers (Crossbows)

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Sword & Buckler troops

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Sword & Buckler troops

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Medium Artillery

1 unit of Sword & Buckler troops

There were 2 sub-generals assigned to command the center. They were under the observation of the Army General, of course.

The left “leg” of the works was protected by the following formations:

1 unit of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

1 unit of Light Artillery

1 unit of Spanish Foot

1 unit of Sword & Buckler troops

Outside of the line of works, but well within the Spanish “zone,” there was a unit of Heavy Artillery accompanied by a unit of Skirmishers carrying arquebuses.

There was a sub-general in charge of this sector.

A small wing of cavalry (1 unit of Knights, 1 unit of Heavy Cavalry, and 1 unit of Light Cavalry) was drawn up on the left, and quite close to the edge of the prepared works. This detachment or division was led by another sub-general.

Very close to the river and road, in the approximate center of the Spanish fortified position, there was a reserve of horse. This formation contained 2 units of Knights and 2 units of Heavy Cavalry. This reserve was under the direct command of a sub-general.

Reviewing the points per type for the Bonus Units in the Spanish (Italian Wars) list on page 18 of Advanced ARMATI, I determined that there were 195 points worth of Spanish troops on my tabletop.

Given that the vast majority of Spanish troops were not going to be moving (they were in a defensive position after all), Control Ratings were assigned to the cavalry on the wings and of the reserve. I gave the Spanish General 4 Heavy Division Control Points and 2 Light Division Control Points. (Sidebar: At this point in the project, I had not drafted scenario rules for the commitment and moving of the Spanish cavalry reserve. I was thinking about a free complex move/wheel that would allow the formation to divide and gallop off to the flanks. Then again, they might be needed to close holes in the defensive line. This was a “to be developed and determined” issue.)

Looking over the deployed Spanish lines, I took a quick count and noted that there were a total of 24 key units present on the tabletop. Under these rules, the starting “army breakpoint” is 2 key units. This number is modified by the number of key units drafted when Bonus Units are purchased. Obviously, this was not your typical ARMATI wargame. At first, I considered a “50% rule,” which would mean that the Spanish would have to lose the equivalent of 12 key units in order to be defeated. This seemed a bit of a “tall order,” so I reduced the number to 10 key units. The French would have to break, destroy, or rout 10 Spanish units in order to win the field.

Following, in general, the verbal and visual descriptions provided in the McArdle summary of Ravenna, I deployed numerous French guns on the right and left of their deployment. Having made quite a few “batteries,” I also placed some cannon in the center. There was French cavalry deployed on the right and left wings. There was a small reserve of 3 units positioned in the center. A strong contingent of Landsknechts was arranged on the French right wing. A long line of French Foot was constructed in the center. These ranks of pike-armed troops stood behind the dispersed line of cannons and interspersed units of skirmishers armed with either arquebuses of crossbows. In more specific detail, the French deployment was as follows.

On the French left wing, the following units were arranged:

2 units of Light Cavalry (Stradiots)

2 units of Heavy Cavalry

2 units of Knights (Gendarmes)

There were 4 units of Medium Artillery arranged in front of these horsemen.

This wing was under the direction of a sub-general.

The center-left of the French main line consisted of:

7 units of French Foot

2 units of Skirmishers (Crossbow)

2 units of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

3 units of Medium Artillery

There was a sub-general assigned to this large formation.

The “hinge” of the French line consisted of the following:

2 units of Heavy Artillery

1 unit of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

The General of the French Army placed himself and his suite of subordinates, messengers and bodyguards behind this “battery.”

Directly behind this “battery” of heavy cannon, there was a cavalry reserve of:

1 unit of Heavy Cavalry

2 units of Knights (Gendarmes)

There was a sub-general in charge of this formation.

The center-right of the French main line was a twin, essentially, of the center-left. It contained:

7 units of French Foot

1 unit of Skirmishers (Crossbow)

2 units of Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

3 units of Medium Artillery

This formation was commanded by a sub-general.

The French right was a bit crowded. This sector contained the following troop types:

4 units of Medium Artillery

2 units of Light Artillery

4 units of Landsknechts screened by 2 units of Allied Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

2 units of Veteran Landsknechts screened by 1 unit of Allied Skirmishers (Arquebusiers)

3 units of “Lesser” Landsknechts

The Landsknechts were led by a sub-general possessing slightly better qualities than the usual French sub-generals.

On the far right, the French cavalry wing included:

2 units of Light Cavalry (Stradiots)

1 unit of Heavy Cavalry

1 unit of Knights (Gendarmes)

This mounted force was commanded by a sub-general.

With regard to Heavy and Light Division Control Ratings, I followed (in spirit anyhow) the rules as written. As I deployed 8 Heavy Divisions on the French side of my table, I gave the French General 8 Heavy Division Control Points. The Light Division Control Points were adjusted in order to allow for the SI units spread out between the “batteries” of Medium and Heavy guns. A quick count informed that I needed 13 Light Division Control Points. (The units of Artillery were not a part of either calculation.)

In terms of points, my addition (and checking of figures) informed that the French had 72 points of Artillery, 63 points of Cavalry, and 106 points of Infantry deployed on the tabletop. This gave the French army an overall strength of 241 points. In terms of key units and Army Breakpoint, the French had 36 key units, so employing the same percentage as figured for the Spanish, the French would quit the field when they had lost 14 key units.

The opposing, if admittedly somewhat crowded, deployment of each army is shown in Map B.

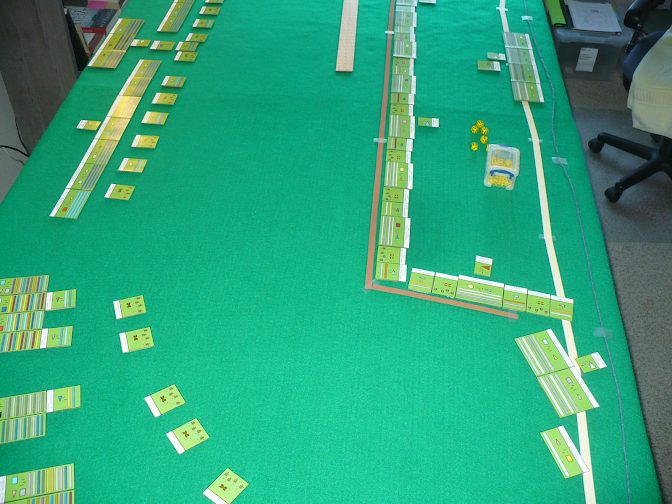

Taken from above the Spanish left and French right, this photo shows the initial deployment of the opposing armies as well as informs of the flat and simple nature of the landscape. The Spanish are in place behind their line of defensive works. They do have a small force of cavalry outside of these works - on both flanks. The French have a line of artillery as well as some skirmishers forward of their main strength. The French have placed Landsknechts and cavalry on their right; the main formation of foot stands behind the cannon in the center, and there are more cavalry positioned on the left wing. The French also have a reserve of horse, stationed behind two “batteries” of heavy guns in the center of their deployment.

A close up taken from behind a portion of the French right, showing the deployed-in-depth and somewhat colorful ranks of the Landsknechts. These mercenaries have some skirmishers screening their front; they also have artillery at least a move in front of their deployment line.

A view of a segment of the main French line, showing the neat order of the French foot “regiments” and the forward line or deployment of the various artillery and skirmisher units.

How It Played

The first few turns of the scenario saw quite a lot of cannon fire but very little effect from these loud and clouds-of-smoke generating discharges. The Spanish guns were rather well protected and the French were firing at long range. The French guns were out in the open, but the Spanish were also engaging from a distance. While this duel was taking place, there was some actual dueling on the wings of each army. The light cavalry formations from both sides galloped into one another and started slashing with swords and or hurling javelins. It was not recorded who drew first blood on the day, but it was noticed that the Spanish cavalry routed a unit of French light horse over on the Spanish right. After some time spent volleying cannon balls/projectiles back and forth, the French moved up their skirmishers to see if they could harass the artillery crews or perhaps even coax the Spanish foot out of their hiding places. (All of the Spanish infantry were prone. They had been ordered to “take cover” from the French bombardment.) This initial advance did not go well for the French. The Spanish guns found the range and used case-shot against the enemy arquebusiers and crossbowmen. No fewer than 3 units of French skirmishers were subjected to a hail of fire and as a result, were encouraged to leave the field.

Turns 4 through 6 witnessed more action across the field/table. This is perhaps best summarized by moving from the French left wing over to the French right. The French light cavalry were defeated near the marshy ground and so, half of the French heavy horse were ordered to move up. The Spanish cavalry used this time to rest, reorganize, and think about sending one regiment to charge the French guns, but from the flank. The artillery duel between the French left and Spanish right continued without let up. On rare occasion, counter-battery fire would score a hit, but due to the distance, these hits were marked as fatigue instead of actual casualties. In the center, the French foot, tired of doing nothing as well as a bit anxious, were finally ordered forward. This long line of French infantry passed through the majority of their cannons, thereby reducing the number of “batteries” that could be directed to keep firing on the Spanish line. Over on the French right, things were going rather well. The Spanish light cavalry had been forced to withdraw to the river, and the heavy cavalry was being pummeled by a combination of Gendarmes and some Landsknechts, who had joined the confused melee. In fact, many of the Landsknechts units were making good progress toward the Spanish works. This advance would bring them face-to-face with the Spanish foot and their supporting cannon, but given their experience and fighting ability, the Landsknechts were confident of success.

A later view of the French right and Spanish left, showing the advance of the Landsknechts as well as the forward movement of the French skirmishers toward the defensive works. The cotton “kapoks” indicate units which have fired. The white dice behind these units remind me of the next turn they will be able to fire. Notice that the Landsknechts have decided to stop waiting on the guns and have advanced through this line to begin their attack on the Spanish line.

The next three turns of the battle saw continued and developing success against the Spanish left. What remained of the Spanish cavalry was destroyed in a sharp melee against many enemy soldiers, both on foot and mounted. The Landsknechts made their first assault, braving sheets of fire from various guns and units of skirmishers carrying arquebuses. A few holes were created in the Spanish line as two gun emplacements were overrun and a unit of LHI (sword & buckler troops) were routed. Noticing the threat to his left flank, the Spanish general ordered 2 units from his cavalry reserve to shift over and shore up that part of the line. In the center, the general advance continued. With the French cannon screened by their troops, the Spanish crews had no real worries about keeping their heads down. In fact, some of the Spanish skirmisher units got off the ground and added their “weight” to the developing contest. More French skirmisher units paid a steep price, and several of the larger foot units felt the deadly sting of well-aimed Spanish artillery. Meanwhile, over on the Spanish right, far away from the Landsknechts, the cavalry battle grew in intensity. The French horse were being challenged. The French general on this side of the field gave orders for the rest of his cavalry to wheel around and get ready to assist in this local contest. (Map C shows the state of the table at the conclusion of Game Turn 9.) Over the course of the next several turns, the battle was decided. Unfortunately, things did not go well for the French.

Here, the Landsknechts have braved the defensive fire of the Spanish guns and skirmishers, and have begun to breach the breastworks, at least in this sector of the field. The French infantry have also started moving forward, though later than the mercenaries on their right flank. These attacks screen the supporting artillery, leaving the various foot units exposed and vulnerable to concentrated enemy artillery fire.

The Landsknechts continued to push forward against and into the Spanish left. Indeed, from above the chaotic fighting, it looked as if a fatal gap or series of gaps had been torn in the defensive works. Landsknechts were pouring over and into the Spanish position. There were even companies of the veteran fighters engaging with the leading elements of some Spanish heavy cavalry and knights who had galloped over from the reserve. Significant advantage could not be taken however, as it was rather a “traffic jam” of opposing units. Landsknecht formations found themselves locked in a death struggle and not on the best terrain. Given the confined space, it was difficult if not impossible, to shift attacking units where they would do the most good, or do the most damage. Over on the other side of the field, a second large cavalry contest began. Fresh units of French horse engaged with wounded but rested units of Spanish. A total of 5 regiments were involved in this swirling melee; the Spanish had one more unit than their enemy, but again, the Spanish units were damaged from the previous fighting on this flank. In the center of the field, the French line finally reached the breastworks. They did not have enough movement left to engage and so, had to wait another turn. This allowed the Spanish artillery to deliver a series of point-blank salvoes. The Spanish skirmishers could not miss from this distance and at such a large target. More than several score Frenchmen were put out of action by case shot, withering arquebus discharges, and deadly crossbow bolts. Their ranks now a bit ragged looking, the French foot clambered over the works and began fighting against the now standing and prepared for battle Spanish troops. Up and down this long line the melees raged back and forth. The French fought bravely, but they could not get any real purchase on the other side of the defenses. The Spanish artillery crews fought as well as they could, and the Spanish skirmishers joined in to help out their “heavier” brothers in arms. In almost every local contest, the Spanish skirmishers and crew were swatted away like so many annoying horse flies. The Spanish foot, however, remained in position and fought stubbornly. During Turns 11 and 12, the French would see 5 of their foot units break and run. This left gaps in their once pretty and proud line; this also caused some of the units next to the routed formations to lose heart. In the next two turns of the scenario, while the Landsknechts tried to expand their “beach head,” and the French cavalry on the left tried to push back the enemy horse, the main portion of the French army suffered many more losses. Their foot regiments had failed to push over and into the works like the Landsknechts. Their foot regiments had paid a very steep price on the day. The failure of the main French attack resulted in a reversal for the army, in a general collapse of morale. The Spanish, at some cost, but certainly not as much as paid by the French, had won the day. (Map D shows the state of the table at this point.)

Comments

In the historical battle, the French army was victorious, and if the figures in the Wikipedia entry are accepted, then the Spanish suffered over 50 percent losses. In this scenario, based loosely on the historical engagement, the result was reversed. While the French were contesting the Spanish right and had scored a local success on the Spanish left, the wargame was lost in the middle. French casualties were roughly three-times greater than those inflicted on the Spanish.

Obviously, this latest project was different from my usual ancient fare. Instead of having hoplites or phalangites or cavalry and perhaps a few elephants on my tabletop, participating in a set-piece battle, I prepared modern troops. There were gunpowder weapons present, and the battle was an attack on a prepared position. I did not experience “culture shock” for lack of a better term, but I did wonder about the ability of the selected rules to sufficiently handle such a wide expanse of time and such a wide variety of military conflicts and systems.

About three turns in, I started recalling my “horse & musket days,” when my focus was on Napoleon, or Cornwallis, or Frederick the Great. I wondered about the “every other turn” firing restriction on artillery units. I wondered about the impact and morale effect of artillery (even if primitive by early nineteenth century standards) on columns of troops. For example, on a couple of occasions, I wondered how the Landsknechts would really react when the Spanish guns, from basically point-blank range, belched their iron projectiles. First, it was odd that more than once, the Spanish dice indicated a miss. When hits were scored, I wondered why the targeted infantry (or cavalry) did not pause, recoil, or seek to avoid the firing lane(s) of the enemy guns. Staying with the desperate action on the Spanish left, I wondered why the unengaged Spanish units were not permitted to adjust their positions. It seemed unrealistic or implausible for Spanish units defending the works to simply ignore the advancing enemy foot as they passed them by on this or that flank. Right, wrong, of just not informed well enough, it seems to me that fighting in and around breastworks will be more chaotic and confusing than melees conducted on open ground.

With regard to the fighting across the defensive works, I studied the linear obstacles paragraph in the rules. For consistency and ease of play, I decided to use the flank/rear fighting value of the attacking units while the defenders were able to use their frontal fighting value. I briefly considered penalizing the attackers by having them use their “special melee circumstances” value, but this struck me as too lopsided. Reflecting on the recently concluded scenario, it appears that the Landsknechts has better luck with the dice than the French foot enjoyed. This made me wonder if I should have drafted separate scenario rules that would have better covered this eventuality. For example, attacking the works would have been a three-step process. First, there would be the initial attack, where the advancing unit would be at a disadvantage. Second, and perhaps based on a competitive die roll, the attackers would be able to push back the defenders and by so doing, be able to fight on more even ground (i.e., using their frontal fighting value instead of the lower flank/rear fighting value). The third step might see both sides being marked as “un-dressed” or disordered, given the confusing nature of fighting in and around works. Along this same line of thinking, I suppose I could have taken a closer look at the participation of artillery crews and skirmishers when defending breastworks against attacking lines of enemy foot.

In addition to the presence and involvement of units using gunpowder weapons, this based-on-history-but-not-strictly-historical scenario was different because it was not a general engagement. This was an attack on a prepared position. As a result, obviously, the French shouldered most of the responsibility of moving the battle forward. I believe I gave the French and Spanish sufficient time to conduct their artillery duel or exchange. (It occurs to me that I might have allowed for some guns to misfire.) The French had to win. The Spanish only had to not lose. As the battle progressed, I wondered about command and control. I have already mentioned my “concerns” about the Spanish not being able to respond to local emergencies and developing situations. I wondered if I should have allowed the French and Landsknechts more flexibility. While the Landsknechts did well on their side of the field, the inevitable traffic jams prevented exploitation of the advantages won, which allowed the Spanish to shift some heavy cavalry over and cover this breach.

In summary, this was an enjoyable distraction or diversion from my usual concerns of chariots, elephants, legionaries, and pike phalanxes. As with any wargame project, there were pluses and minuses, as well as subjective assessment(s) of this and that point or subject. Admitting that the overall experience might be representative of a lack of ability on my part, it occurs to me (or occurred to me early on in the wargame), that this type of scenario, that this type of contest might be challenging to conduct and play using the ARMATI rules. I wondered if Pike & Shotte might have been a better choice. I wondered, too, if it might be worth the investment to look for and purchase a more specific set of rules for wargaming the Italian Wars or more generally, conflicts between 1500 and 1700.

Notes

- Befuddled and bothered by my inability to make any appreciable progress with a Blore Heath idea/project, I put the various drafts and other papers into a box and then put the box in a bin. The bin was placed in storage. One could remark that this sudden interest in the Italian Wars was a way of dealing with (or not dealing with) this subjective failure.

- The September 1991 issue of Miniature Wargames (Number 100) contains a detailed Index of the articles, reports, and other pieces published in the Issues 1-96 of this signature hobby magazine.

- Number 82 was published in March 1990. As I type this, the end of 2022 is rapidly approaching. So, simple math informs that at least 32 years have elapsed. Allowing for cross-Atlantic delays and so forth, let me round down that length of time to three decades. I do not have exact records, but I cannot imagine that I read this article more than a few times in those 30 years.

- To get some additional ideas and information about Ravenna, I did a quick search of the Internet and found the following sites/links: https://balagan.info/battle-of-ravenna-11-apr-1512, https://olicanalad.blogspot.com/2008/05/ravenna-1512.html, and https://olicanalad.blogspot.com/search/label/Italian%20Wars. Of course, one can also spend some time reading/studying the Wikipedia page. Please see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Ravenna_(1512).

- At the bottom of page 10 of his excellent, recommended and I would argue must-have book, Battle Notes for Wargamers, Donald Featherstone explains: “To refight any historical battle realistically, the terrain must closely resemble both in scale and appearance the area over which the original conflict raged, and the troops accurately represent the original forces.” My intention was neither to build exacting terrain nor to accurately depict the armies present on that day. My goal was to set up and play an Italian Wars wargame. By this solo effort, I hoped to banish the “bad memories” of Blore Heath.

No comments:

Post a Comment