MESSING WITH MAGNESIA

Rather than simply replicate the admirable, excellent, and traditional refights of the historical battle between Ahenobarbus, Antiochus and others, [1] I thought and hoped that it might prove entertaining as well as interesting to go in a different direction. Instead of staging a Featherstone-quality refight [2] of the 190/189 BC clash between an empire on the rise and one on the decline, I would use the historical contest as a “blank canvas” upon which I would attempt to paint. [3] This solo wargame or project would feature armies that were roughly twice the reported size of the original forces present. As I like having elephants on my table when I can, I multiplied the reported number of these animals by a factor of five. This project would mark my fourth attempt at constructing a “miniature” battle based on the historical contest. In the previous attempts, dispiriting if educational failures all, it might be remarked that Magnesia was messing with me. [4]

Starting Points

In his brief analysis of Magnesia, provided on pages 197-200 of LOST BATTLES—Reconstructing the Great Clashes of the Ancient World (a very interesting read and highly recommended), Professor Philip Sabin summarizes the existing narratives of the ancient authors. According to his reading of Livy’s account, “The Romans fielded 4 legions (2 Roman and 2 Allied), 3,000 Pergamene and Achaean peltasts, 3,000 Italian and Pergamene cavalry, 1,000 Cretan and Trallian skirmishers, 16 African elephants, and 2,000 Macedonians and Thracians who were initially posted as camp guards.” Doubling these numbers would give me 8 legions, 6,000 peltasts, 6,000 cavalry, 2,000 skirmishers, and 4,000 camp guards. As mentioned above, the reported number of pachyderms would be multiplied by 5, resulting in a herd of around 80 animals. Along with the professor’s scholarly work, I referred to the orders of battle created by S. J. Randles as well as the orders of battle developed by the “triumvirate” of Robert Burke, Mitch Berdinka, and Doug Lange.

A similar approach was taken when assembling the Seleucid host for this revised version of the historical battle. Strict adherence to the doubling “formula” would not be possible with regard to Professor Sabin’s numbers (also taken from Livy’s narrative account), as this would require the preparation of 43,000 assorted skirmishers. At the proposed scale of 1 “figure” equals 50 real men, I would need to make 860 skirmishers! The cavalry numbers would not be as overwhelming, but would still be considerable. For this “model” of an imaginary battle, I would need to organize 12,000 cataphracts, 5,000 Galatians, 2,400 Dahae horse archers, some Tarentines, as well as 4 units of horse guards, each with a strength of 1,000 troopers. For the infantry contingents, I would need approximately 32,000 phalangites and 6,000 Galatians warriors, along with 9,400 Cappadocians and mercenaries. In addition, there would be a “block” of 10,000 Silver Shields (Argyraspides), and a collection of Indian elephants approximately three-times the size of the Roman herd. There would also be a number of Bedouins riding camels as well as quite a few scythed chariots. Once again, as I digested these numbers and formation strengths, I looked over how Messrs Randles, Burke, Berdinka, and Lange translated the information to their respective tabletops.

Readying the Romans

Adapting the work completed by Robert Burke and associates and then adjusting the listed dimensions for figure scales and unit types provided on page 1 of the Tactica II rulebook, I prepared eight functional albeit two-dimensional legions. Four of these formations were Roman, and four were composed of Allied or Latin troops. Each legion, depicted with a representative scale of 1 “figure” equals 50 “real men/soldiers,” consisted of: 1 base of 24 Velites (measuring 8 cm x 3 cm); 1 base of 24 Hastati (measuring 6 cm x 1.5 cm); 1 base of 24 Principes (measuring 6 cm x 1.5 cm), and 1 base of 12 Triarii (measuring 6 cm x .75 cm). At the established figure/unit scale, each legion represented approximately 4,200 men. [5] The eight legions would represent the equivalent of around 24,000 heavy infantry and 9,600 Velites. With regard to command and control, there would be several praetors on my table. (Each praetor would be responsible for a pair of legions.) There would be two consuls, with one of these veterans of the senate nominated as the overall commander of the army. In addition, there would be commanders for each wing, and there would be a commander or two for any additional division not already covered. On my extended tabletop, these assembled-for-battle legions would occupy a frontage of approximately 65 to 85 cm, leaving either 255 or 235 cm of space with which to work. [6] Turning to the cavalry, light infantry contingents and other troops, I reviewed the work done by S. J. Randles, the aforementioned analysis provided by Professor Sabin, and a few other sources. Given my “expanded edition” of Magnesia, it was noted that I would need to fabricate 600 Roman cavalry, 2,400 Latin cavalry, 200 Achaean cavalry, 1,400 Pergamene cavalry, and 1,000 Numidian cavalry. With regard to foot troops, I would need to prepare 2,000 Achaean peltasts, 4,000 Pergamene peltasts, and 1,000 skirmishers divided evenly between Cretan archers and Trallian slingers. Increasing the size of the Roman elephant herd by a factor of five, as I previously stated, I would need to build the scale equivalent of 80 African elephants.

Adhering to the figure/unit scale, I would deploy 1 unit of Roman cavalry containing 12 “figures.” The Latin cavalry would number 4 units, each of 12 “figures” as well. The small contingent of Achaean horsemen would be integrated into the Pergamene cavalry, which would be depicted with 2 units, each 16 “figures” strong. The Numidians would ride into battle with 2 units, each unit having a strength of 10 “figures.” For the peltasts, I would not be able to match the numbers exactly, so I prepared 2 units of 18 “figures” each for the Achaeans and 6 units of 12 “figures” each for the Pergamene contingent. The skirmishing missile troops would be “modeled” with 2 units, each having 10 “figures.” After some back and forth with myself (the Tactica II rules do not provide a figure/unit scale for elephants or chariots), I settled on 1 elephant stand being the approximate equivalent of 12 animals. To represent the inflated Roman herd, I would produce 7 stands, deployed into units of 2, 2, and 3 stands, respectively. [7] In checking over Robert’s orders of battle, I almost overlooked the large unit of FT (Italians) that were attached to the 1st Latin Alae. Just in case I needed some additional troops to shore up the Roman line, I prepared 3 units of these troops. However, these units were 36 “figures” strong instead of 48. They were also deployed as their own division or command.

Sorting the Seleucids

If I doubled the number of skirmishers reported by Professor Sabin on page 198 of his book, I would have around 9,000 more missile-armed troops than the 33,000 men, approximately, filling the ranks of the Roman and Allied legions. So, in order to avoid a surfeit of skirmishers, I decided to keep the strength of this contingent the same. Applying the same figure/unit scale, I would still need to prepare and organize 430 skirmishers into various formations. For the sake of expediency, I made all of the Seleucid skirmisher units that same strength as the Roman/Allied Velites. Rounding up, this gave me or required the preparation of 18 units of skirmishers. Initially, I thought to divide these evenly between archers, javelineers, and slingers, but then decided to limit the number of javelin-armed skirmishers to just 4 units. The Seleucid cataphracts were next on my list. For sake of consistency as well as for ease of production, I built 10 units of 24 cataphracts, each unit arranged in 3 rows of 8 “figures.” As it would be taking too much historical license to swell the ranks of the Argyraspides (Silver Shields) to 20,000, the strength of this formation remained unchanged. After thinking about it for a bit, 4 units of 48 “figures” were constructed, with each unit having a frontage of 8 “figures,” and a depth of 6. The main phalanx was increased to a strength of 30,000 pikemen and “modeled” with 10 units of 60 “figures” arranged in 10 ranks of 6. [8] Switching gears briefly to address the cavalry contingents, I started with the Tarentines. Two units of 10 light cavalry were assembled. The Galatian horsemen were represented with 4 units of light cavalry, each unit being 10 “figures” strong. Five units of Bedouins riding camels were prepared. Each of these units contained 18 dromedaries and riders organized in 2 ranks of 9. Half a dozen units of Dahae were built. Each of these small units contained 8 “figures.” The Companions and Agema “regiments” were depicted with 4 units, each 18 “figures” strong and arranged in 3 ranks of 6. This left the light troops and auxiliaries, the Galatian warriors, the elephants, and the scythed chariots. With regard to the first category, I prepared 3 units of 24 peltasts, arranged in 3 ranks of 8, and then 4 units of 12 peltasts, arranged in 2 rows of 6. I also fabricated 2 units of Asiatic auxiliaries, each with a strength of 30 “figures” and organized in 3 ranks of 10. For the Galatians, I readied 2 warbands, each of these having a strength of 40 warriors, arranged in 4 rows of 10. Antiochus and his associates were given 240 elephants. These pachyderms were divided into 20 stands. Eight were deployed as screens, while the remaining 12 were organized into 4 troops of 3 “models” each. For the scythed chariots that were present (and performed rather poorly in the historical contest), I established a slightly different unit scale (1:20) and so, wound up deploying 4 units of these “one-hit wonders.” There were 3 “models” in 2 of the units and 2 “models” in the other squadrons.

Setting the Table: Terrain and Deployments

Speaking as a simple student of ancient military history, it seems that terrain played a very small role, if any at all, in the historical battle of Magnesia. Then again, if one counts weather conditions as a category of terrain, this amateur assessment needs to be revised. For my purposes, however ill defined, I was not interested in trying to model the fog or mist and the impact this dampness would have or had on bow strings and slings. Neither was I interested in recreating the poor visibility resulting from the conditions and the inherent problems this would have on command and control. My larger battle of Magnesia would take place on a day when the sky was clear and the temperature was mild.

I did have an interest in designing a more “realistic” landscape upon which the two armies would engage. To this end, I read with interest a paragraph written by Dr. Chris Winter. [9]

I also found myself drawn to the revised terrain employed by the team of like-minded wargamers in Argentina. [10] With the intent of subjectively improving but not overly complicating my tabletop, I reviewed the terrain rules in Tactica II while simultaneously studying the terrain rules and procedures contained in L’Art de la Guerre (2014 Edition) and IMPETVS (2008 Edition). [11]

I finished landscaping my table in the mid afternoon of May 07. As with my previous reports, the terrain was more functional than aesthetically pleasing or impressive. There was a fordable river on the Roman left, renamed Frigidarius. There was a steep hill in this sector of the field/table as well. Moving to the right along the Roman position, the next feature was a small gentle hill, a patch of scrub, and the ruins of an ancient temple sitting on that gentle hill. Further to the right, there was a larger gentle hill, which was covered at one end with a light wood. There was another patch of scrub, a bit denser than the previous, further to the right of the large gentle hill. At the opposite end of my table, there was another river. This water obstacle was not fordable and would remain anonymous. There were two patches of marshy ground on the Roman side of this river. There was also a fourth gentle hill (more narrow than round) located near what would be the Seleucid left. The accompanying pictures will, I hope, clarify the above description. The accompanying pictures will also show how the opposing armies were deployed for this fictional battle. (Note: I have decided to combine the selected photographs into one section formatted near the end of this post/report.)

The Roman high command placed the Italian cavalry, Achaean light infantry, and Italian levy on the left flank. The horsemen were not right next to the bank of the Frigidarius, but they were close enough. The Achaean peltasts were next in line, reinforced by two dozen African elephants. The “division” of Italian foot was screened by skirmishing archers and slingers. This wing was under the overall command of Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus.

The left end of the legionary deployment was lined up with the aforementioned gentle hill with the temple ruins. The eight legions were arranged in a traditional manner, with three lines of heavy infantry screened by Velites. It was an alternating deployment, in that there was an Allied legion and then a Roman legion, and then another Allied legion, etc. The first consular army was led by Marcus Aemilius Lepidus. The second consular army was under the direction of the overall commander, Lucius Cornelius Scipio. The right end of the legionary deployment lined up with the light woods on the end of one of the gentle hills, so the main Roman line was rather compact but very strong.

The Roman right included Pergamene light infantry and cavalry, Roman and Numidian cavalry, and two formations of elephants, numbering around 60 pachyderms all together. The peltasts and two dozen elephants were next to the legionaries. The Pergamene cavalry was on the right of the light infantry, and the Romans and Numidians held the far right or end of the line. Three dozen elephants were held in reserve on this flank. In contrast to the Roman left, there was a lot of space between the Numidian light cavalry and the marshy ground marking the river on this side of the field/table.

Shifting my attention to the Seleucid side of the table, it would be fair to remark that their assembled formations filled the length of the miniature battlefield, stretching from one river to the other. It also should be noted that the proposed elephant screens were combined into massed units of various sizes. Starting on the far left wing, there were six units of Dahae horse archers. These were joined by Tarentine and Galatian light cavalry, who had the addition support of a “squadron” of scythed chariots. A strong division of cataphracts, accompanied by Seleucus and his subordinate commanders, reinforced the Tarentines and Galatians. Moving right down the line of battle, an “ad hoc” command containing Galatian warbands, Asiatic auxiliaries, peltasts, skirmishers, and another “squadron” of scythed chariots was drawn up. As a screen to this diverse division, there was a line of Indian elephants (14 models in number) that was “bookended” by peltasts and screened by an impressive 7 stands of skirmishers.

The Seleucid phalanx or approximate center of the army was divided into three parts. The left-hand portion consisted of 6 deep blocks of pikemen interspersed with elephants and protected on the left with a unit of peltasts. The formation was screened by some skirmishers. To the right and slightly forward of this command was the central phalanx. This division contained 4 deep blocks of better quality phalangites. Like their comrades to the left, there was a troop of elephants within the phalanx and a unit of peltasts guarding its left flank. A longer screen of skirmishers protected the front of the formation. Philippus stationed himself and his subordinates on the small gentle hill just behind this phalanx. The right-hand contingent of the main phalanx included the Silver Shields. These elite troops were screened by skirmishers and protected on their right by a unit of peltasts. These pikemen enjoyed the support of an attached “regiment” of Agema. There was also a separate command containing 3 elite units of heavy cavalry deployed to the right rear of the Silver Shields. King Antiochus III positioned himself and his entourage very near this cavalry formation.

The Seleucid right wing was assigned to 5 units of Arabs riding camels. These comparatively poor troops were screened by 3 units of scythed chariots. The Arabs were also supported by a second division of cataphracts.

Rule Tweaks

- As I had shrunk the listed dimensions for various troop types by 50 percent, it followed that I would do the same for command radius, movement rates, and missile ranges. Initially, I thought I would make smaller copies of the 15 mm scale ruler provided on page L 22. Then I thought it might be simpler to switch to metric units. The basic command radius would be 12 cm. (This guideline might be subject to change, however.) Infantry would move 8 cm per turn and cavalry would move 12 cm per turn. Unit wheels would be 2 cm for foot and 4 cm for mounted. The “CTZ” or Combat Threat Zone would be 8 cm.

- Under Section 1.2, the basing dimensions for 15 mm chariots is a square stand measuring 40 mm (4 cm) on each side. Using my revision, a chariot base or stand became a square with sides of 2 cm. Unfortunately, I could not make “standard reduction” work. My “model” chariots or depictions of chariots would not fit on this smaller base/stand. In order to establish some kind of visual appeal, the stands of scythed chariots were enlarged. The measurement modifications listed in Number 1 still applied.

- Previous experience informed that skirmishers mounted individually on a 1 cm square base were “fiddly” and time consuming when it came to movement. To facilitate the movement of rather a lot of skirmishers, I took a “cloud” approach. I built units of skirmishers that were 24 “figures” strong. These skirmishers were arranged in 3 “lines” and represented by stands or counters measuring 8 cm by 3 cm. Even though the skirmishers were depicted on a single stand, units could perform the same actions as skirmishers that were based individually.

- It occurred to me that the rout path and “panic zone,” described in Section 7.14, was exactly half the size or length of the “CTZ” or Combat Threat Zone. To make things a little easier for me, I decided to increase the rout path and “panic zone” to 8 cm so that it would match the Combat Threat Zone.

- With regard to panicked elephants and or chariots, I adopted the “Rampages rule” found on page 52 of Version 1.1 of Simon Miller’s To The Strongest! rules. I would need a few d10 then, in addition to a fair number of d6 for the planned battle. Given the special nature of these unit types, I increased the rout path and “panic zone” to 16 cm. I considered doing the same for cavalry formations, but then decided to leave well enough alone.

- In looking over the “special rules” drafted by Robert Burke and colleagues for their version of Magnesia, I decided to adopt, without reservation, the substitution for the normal pursuit procedures. I considered the “missile fire versus scythed chariots” change, but decided not to use this in my scenario.

- Instead of applying the stated 25% reduction or “decrement” to melee taking place in a certain type of terrain, I drafted amendments calling for a 10%, 20% or 30% reduction, depending on the terrain feature contested. For example, on my quasi-historical battlefield, one area of scrub would have a 10% reduction to melee dice, while the patch of light woods would see a reduction of 20%.

- As of this typing, early in the morning of May 08, I have still not decided if I want to use the rules-as-written with regard to army breakpoint or make the adjustment to a sector breakpoint, which, depending on the status of the field, may see the collapse of army morale when the required number of sectors are broken or routed.

Summary of the Contest

Noting with some concern, it must be admitted, that they were very weak on their right wing, the Roman commanders still ordered a general advance. These orders applied to all formations except for the Pergamene, Roman, and Numidian cavalry on the vulnerable right wing. These units were held in place until circumstances forced their commitment or redeployment.

First blood on the day was drawn on the Roman left when a unit of Italian cavalry advanced to within spitting range of the Arabs and their camels. The Arab archers let fly and a few dozen Italian riders tumbled to the ground. As the rest of the Italian command came forward, the Arabs suddenly could not find the range. There was no melee between the two formations, at least not yet. There was, however, an unfortunate meeting between some scythed chariots and a group of Achaean peltasts accompanied by a few African elephants. The chariot horses and drivers were decimated by the volley of javelins delivered by the light infantry. In the ensuing melee, the peltasts made short work of the surviving vehicles. In a matter of moments, what remained of the scythed chariot squadron turned tail and routed into the serried ranks of camels and their riders. This initial and local success was countered by the losses suffered in the chaotic melee against the scythed chariots and additional losses suffered from another successful arrow volley, which landed dead center on a unit of Italian levy foot.

As the Seleucid right and Roman left were warming up, the Velites and skirmishers in the center of the large field exchanged a variety of missiles as the distance between the opposing lines closed. Groups of Velites and Seleucid skirmishers dashed in and around the ruins of the temple while javelins, sling stones, and arrows filled the air. More missiles flew between the main lines as the heavy infantry of both sides cheered their brothers on. While nothing was decided, it appeared that the Seleucids held the advantage at this early stage of the battle. The Velites just couldn’t find the range. The Pergamene light infantry did a little better when they came up against a veritable wall of Seleucid skirmishers around the light woods on the one gentle hill. To be certain, the peltasts were a little more interested in and concerned by the large number of elephants walking behind the extended formation of enemy skirmishers.

By the end of Turn 6, it would be fair to remark that a curtain had come down on the Roman right wing, and that a second act was about to begin over on the Roman left. To continue the theatre analogy, the lead characters were engaged in some heavy dialogue in the center of the stage. “Clever” word play aside, the disordered Numidian cavalry had been routed completely by the “steamrolling” scythed chariots. The single Roman cavalry unit was the only formation standing in the path of the Seleucids. Eumenes, seeing the numbers were very much against him, turned around the Pergamene heavy cavalry and ordered them to move behind the main Roman line. Even though one unit of Galatians had been destroyed in melee, the rest of the light cavalry was rather disorganized and could not press the local advantage. The Dahae horse archers had just wheeled their line into a column and would take a few turns if not more to become a real threat to the Roman right rear and rear. The cataphracts were prevented from making a sweeping move by their slower rate of movement and the various friendly light cavalry formations.

At the same time, over on the Seleucid right wing, the Arabs collapsed in a series of melees against Italian cavalry, peltasts, elephants, and levy foot. An unfortunate local command decision saw a unit of cataphracts (one that had just performed a complex wheel and so, was in a state of disorder) run into by some panicked camels. A very bad control test (double 1s) witnessed the panic spread to the cataphract horses and they bolted from the field as fast as they could. Several strong units remained however, and King Antiochus was not too far away with three more units of elite heavy cavalry.

The center of the large battlefield saw more back and forth, even as the Silver Shields and Hastati from two legions came to grips in and around the temple ruins. The regular phalangites were making some progress against the Roman first line, but again, this was becoming a battle of attrition. The one troop of Seleucid elephants maintained its impetus bonus, but the bloodied Hastati scoffed at the colorful and trumpeting animals. Ironically, the poor quality pikemen scored a couple of local successes when they routed two units of Hastati. Surprised by this development, most of the victors (and their elephants) did not pursue, but on the left of this local contest, a package of pikemen and pachyderms pursued into the ready and waiting ranks of a formation of Principes.

Ideally, I should have liked to play 9 or even 10 turns, but I found it difficult to rationalize extra time and effort once I had finished the melee phase of Turn 8. As it had been for two or three turns, the Roman right was no more. The sole unit of Roman heavy cavalry had been trampled by a unit of cataphracts, these armored horsemen relieved to finally be involved in the larger battle. Eumenes continued to redeploy his Pergamene lancers. There was some question as to whether he would eventually wheel these formations around and present a local line of battle for the pursuing Seleucids. This would have been a brave but foolish move, given the numbers of light cavalry that were chasing the Pergamene troopers. Let us not forget the scythed chariots and slower cataphracts.

The Roman near-right was no more as well. A line of Seleucid elephants, certainly not as orderly nor as pretty as the one which started the battle, was moving deeper into this zone and would be capable to threatening the exposed right flank of heavily engaged legionaries. There was also a fresh command of various troop types following the lumbering pachyderms, though their timely arrival at any point of actual fighting was doubtful.

Over on the Roman left, the Italian cavalry (what remained) and the Italian levy had their hands more than full in trying to fight the solid formations of cataphracts. Although slower moving than most cavalry, these armored horses and riders had secured impetus in two of the melees and were cutting large swathes into the defending formations. In a brief and terribly one-sided cavalry contest, the Italians were bowled over and the routing survivors generated disorder in nearby friendly units. It appeared quite obvious that King Antiochus enjoyed a substantial advantage on this flank or wing, even though several Roman and Italian formations were still present and fighting.

In the center of the field or tabletop, in the zone between the elongated hill with the patch of light woods at one end and the small, gentle hill with the temple ruins, the Roman legions were absorbing body blow after body blow in what could be described as a hard-fought series of contests between several heavyweight boxers. The first line of Hastati had done little to slow down the advance of pike phalanx and pachyderms. The second line of Principes did better, but found it as hard to handle the numbers ranged against them. In some instances, the legionaries were able to punish the pikemen only to be nearly crushed by the accompanying elephants. In other melees, the legionaries were able to hamstring and then slaughter quite a few pachyderms but find themselves skewered by several ranks of pike points. One bright spot in this chaotic and deadly battle in the center was when a troop of elephants panicked and ran through a couple of phalanxes. The resulting disorder was fairly significant, but the nearby Roman legions were in dire straits and not able to capitalize on the situation. The line of Principes was under quite a bit of pressure. A decision had to be made regarding the commitment of the Triarii. Having received urgent messages about the condition of his right wing as well as couriers bearing news about the status of his left wing, Lucius Cornelius Scipio decided that the day belonged to the Seleucids. Orders were issued to disengage and withdraw before the Seleucid cavalry approaching from the right could make things very, very difficult for the surviving Romans.

Comments

Looking to the printed copies of previous refights of Magnesia for some help as well as a little inspiration, it was noted that Mr. Randles offered two concise paragraphs in his ‘Conclusion.’ Dr. Winter was a little more ambitious and detailed, offering several paragraphs in response to asking how the selected rules played and then examining the age-old question of legion vs phalanx under ‘Thoughts and Observations.’ Mark Grindlay did not offer a traditional summary, at least in my opinion. Instead, he provided a page worth of thought-provoking material in a final section subtitled ‘Historical Debate.’ In the brief recaps of the two games played by his colleagues, the Armati rules—and the scenario amendments—appeared to handle the historical refight very well, although Mark did report that the second game was not as enjoyable and satisfying as the first staging.

I am afraid that I cannot limit myself to just two paragraphs. I confess to liking Dr. Winter’s format and may well borrow that to wrap up my own amateur and solo effort. I admire the additional analysis provided by Mr. Grindlay, although I admit to being a tad green with envy because I cannot phrase my thoughts as scholarly and succinctly. So what to do? How to proceed? In an initial draft of this section, I attempted a question and answer format, sort of an interview of myself regarding how the game played. I asked myself what were the “negatives” and “positives” that I took away, did I think the project enjoyable, historical, realistic, and so forth. As one might guess, this format or idea did not go so well. In another draft, more of an idea really, I considered not typing an end to the report. I wondered, briefly, what impact the lack of a “proper conclusion” would have on the three or four dozen individuals who were courageous enough to read this post all the way through. After stressing over this “problem” for a few days, I thought it might be simpler just to offer a comment or two and perhaps a remark about each main section of the report. So here goes.

I suppose it could be commented or argued that I set myself up for failure by making the opposing armies so large. I could very well be taken to task for selecting a perfectly good historical battle and messing with it, if I may recycle the title of this post. A close look at the provided orders of battle will reveal that the Seleucid center was stronger than the entire Roman army. Given this, a balanced scenario or even-points-per-side wargame was not going to happen. The deployed armies were indeed rather large for a solo wargamer to command and control. If my counting was correct, every turn, I had the option of moving 57 Roman units and 85 Seleucid units. Admittedly, this solo wargame was not played to an official conclusion, that is to explain, where one army was actually routed because it reached its determine breakpoint as written in the rules. Even so, this “called at the end of Turn 8” solo wargame was a subjective success, as it ran for twice as many turns as any other attempt at staging a version of the battle. It might also be called a subjective success, as it gave me more experience with the Tactica II rules as well as permitted me to study Magnesia in greater depth.

Even though I placed more terrain features on my modified battlefield, terrain did not play a major role in this counterfactual contest. There was no incursion on the Roman left by enemy light cavalry that managed to get across the Frigidarius. There were very few problems experienced by either side in negotiating the various types of terrain. On the Roman near-right, there was an extended local battle between some peltasts and skirmishers within a patch of light woods. Towards the end of the engagement, a couple of phalanxes began to enter these woods. However, the possession of this terrain feature did not determine which side won in this local sector and certainly did not determine which side won the larger battle. Across the center of the field, I suppose I could be chastised for not being more strict with respect to the local battle taking place around the temple ruins. Initially, this was a skirmisher versus skirmisher struggle. Then, after these troops withdrew, the Silver Shields and Hastati took their turn. In strict terms of realism and historical precedence, I rather doubt that formations of Silver Shields would bother with moving in or around some temple ruins during an actual battle. I do not have a similar level of doubt about the Hastati or their supporting Principes. In fact, I think the legionaries might be rather comfortable in such an environment. The temple ruins, albeit plain looking and two-dimensional, were positioned to add a kind of “flavor” to the look of the battlefield. The ruins were not really considered terrain. On reflection, perhaps I was mistaken in not considering the possible impact(s) of the remains of this “built-up-area” more carefully. On the whole, I think the terrain served its purpose well. The large and flat green expanse was broken up; a certain appeal was achieved, and each army took the lay of the land into consideration when deploying its forces.

Looking back on the deployments of each army, I think it could be argued that the opposing arrangements were fairly historical. Both the Romans and Seleucids set up their armies with infantry in the center and cavalry on the wings. I continue to think and wonder about the Roman deployment, however. A consular army is an impressive force, as the historical record will support. To be able to field two consular armies on a tabletop and have room to spare, was quite an opportunity. Then again, I wonder about the accuracy of this deployment, given the reportage frontage of a legion deployed for battle. [12] Upon further reflection, I wondered why, when facing such numbers, the Roman command did not seek out better terrain or even prepare temporary fortifications so as to strengthen its position. Turning briefly to the Seleucid side of the field or table, this was a case of not having quite enough room to deploy all of the formations for battle. While the wings were primarily of cavalry or camelry, and some units supported or screened by scythed chariots, the distances involved, especially on the Seleucid left, did not permit a “sweeping envelopment” of the Roman right and by extension, the rest of the army. Here, I will restate my rank as an amateur student of ancient military history. In the reading that I have done, it seems to me that successful flanking moves or flank attacks occur in a much shorter space of time than was the case on my tabletop. Here again, I wonder if the employment of a different set of rules would have addressed this development in a more efficient or satisfactory manner. It was unfortunate that a couple of the Seleucid commands were not able to partake in the battle. The mixed “division” of Asiatics and Galatian warriors on the left was always following front line units, and the small command of elite cavalry accompanied by King Antiochus III got closer to the fighting, but never committed any of its four units to action. On the plus side, I thought that the depiction and deployment of the Seleucid phalanx, that is, the three sections of it, was rather accurate and historical.

Mr. Randles had the time and energy to refight Magnesia three times. [13] As reported above, I was only able to manage one staging, and an abbreviated one at that. The gentleman’s perseverance made me wonder how my attempt might have gone had I not bothered with any rule tweaks. His experiences also made me wonder what impact the drafted rule tweaks had on my “reconstruction.”

Taking the eight adjustments, amendments or revisions in order, I think the scale or size reduction worked very well. The minor exception to this assessment was the small problem of tracking casualties to chariot and elephant units. This small problem should be easy to fix if there is a future scenario featuring similar formations, say, perhaps, Galatians versus Seleucids.

However, I did note a few instances of “issues” with the command distance rules and procedures. These guidelines will have to be closely reviewed if another large Tactica II contest is contemplated. The modifications made to the scythed chariot stands did not, I believe, have a negative impact on the course of the “miniature” battle. In fact, I am not sure there that there is another “work around” for this particular issue. Moving on to skirmishers and their representation, the decisions regarding this troop type did run into some “problems” or lead to some additional questions as the action unfolded. In several instances, formed enemy units made contact with or were able to move into units of enemy skirmishers that had not, for whatever reason, decided to evade in the previous sub-phase of the current turn. Per the rules, at least my understanding of them, the skirmishers that were contacted were removed, as skirmishers cannot stand up to formed or massed units in open terrain. As I had built my units into single stands or counters of 24 “figures” in 3 irregular ranks, these occasions of contact often resulted in enemy massed units still being in contact with “clouds” of skirmishers. This “problem” did not tilt the battle one way or the other, but it did give me pause and made me wonder about the role skirmishers played, broadly speaking, in ancient warfare. In the eight turns that were completed, the opposing lines of skirmishers focused on trying to out-shoot the enemy skirmishers and then getting out of the way when the heavy foot of each side were ready to engage. Advice and counsel provided by the experts on the Tactica II Forum was helpful, but it is obvious that I need to pay more attention to this aspect of the rules should they be employed again. (I also need to pay better attention when drafting, checking, and then preparing the orders of battle. I was slightly chagrined to discover that I shorted the Roman army 500 Cretans and 500 Trallians.) The changes made to the length of the rout/panic zone and to the action of panicked chariots or elephants added a “nice bit of chrome,” I think, to the solo wargame. To be certain, the revisions are not perfect. If another large battle is staged, I will certainly take some time to revisit and tinker further with these changes to the rules as written. Along the same lines, I think the amended pursuit rules, provided by Bob and his friends, worked rather well. Ironically enough, I am thinking that it might prove worthwhile to try and follow his suggestions regarding Magnesia to the letter. [14] Coming to the end of my short list of tweaks, it appears that I did not have a proper chance to use the modified “decrement” rule for melees taking place in or around terrain that is really not suited for massed units of foot or cavalry. Here, I am recalling the contest between the Hastati and Silver Shields in and around the ruins of that temple on the gentle hill. Finally, my lack of a decision regarding the army breakpoint rule did not matter, as I made the decision to call a halt to the scenario based on the status of the field/table at the end of Game Turn 8. There is no question, however, that this decision was also based on the lack of viable Roman units on either flank as well as on the condition of the legions in the center of the field/table.

I will end this admittedly long section with a multi-part question. Was the reported wargame enjoyable, historical, and realistic? Answering this question in the order it was asked and acknowledging that there might be a bit of “politician” in my response, I will offer a “qualified yes” to all three categories.

The staged solo wargame, even though it was not a strictly historical refight of Magnesia, was enjoyable. (If pressed to grade or rate it on a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is not at all enjoyable and 10 is really wonderful, I would give the recently “completed” scenario a 6.5, perhaps a 7. [In the past, I was sometimes called a hard grader by students.]) I will readily admit to being more invested in the preparation of the game than in the actual playing of it. The excitement or novelty of having to move up to 130 units each turn can tax even the most dedicated solo enthusiast. I found the requirement for handfuls of dice to resolve missile fire and melee to be somewhat taxing as well. While there is something to said for tracking losses through attrition (some turns saw rather lopsided results with no apparent effect on morale), I have discovered that I am more interested in using one or two dice, unit factors and perhaps some additional modifiers to resolve a combat. I think that I am also partial to additional grades or qualities of formations as opposed to just three. Granted, these additional grades can complicate things a little, but I think the added “chrome” is acceptable as long as it is not “smothered” with additional handfuls of dice. At the risk of turning this present paragraph of the response into a critique of the rules, I found the movement rules a bit restrictive. To be sure, there is a degree of irony here, as I “grew up on” Arty Conliffe’s Armati rules, which employ a fairly similar system of movement. Shifting the focus to a wider perspective, I also found the solo wargame enjoyable because it provided a welcomed, if also temporary distraction, to current events as well as dealing with the short and long-term consequences of Life choices. I think it is interesting to note or at least suspect, that as I have aged, it appears that my focus or enjoyment of the hobby seems to have shifted from the playing of a wargame to the preparation of a wargame. I know, I know . . . How can you separate the preparation from the playing?

While the vast majority of ancient wargamers will probably neither applaud nor approve of my approach, I think that a large number of them would agree that the scenario was a historical wargame. I based my project on a historical engagement that was written about by ancient authors and studied by modern scholars. To the extent that it was possible, historical formations and tactics were also used, so the staged wargame ticks another box in this category. On the other hand, the scenario was not historical because it was a counterfactual. I am not aware of any battle between the Roman Empire and the Seleucid Empire that saw 8 legions and supporting troops take the field against approximately 40,000 pikemen, supporting troops, and some 12,000 cataphracts. Regarding the depiction and deployment of the Roman and Allied legions, I wonder if the prescribed method or representing these formations was historically accurate? Once again, I wonder and worry about the frontage that would have been occupied by such a force. By and large, though, I think the contest was more historical than not.

Drawing this long sub-section to a close, it seems to me that if I ask a question about “how realistic” the staged battle was, I could recycle some of the same remarks made regarding the historical characteristics of the scenario. For example, it was realistic to see Romans engaged Seleucids on a “model” battlefield. It would not have been realistic or historically accurate to see Romans engage an army led by Charles the Bold. Visually, the realism of my fictional scenario may have suffered from the lack of traditional three-dimensional, well-painted and mounted-on-flocked-bases figures. At the acknowledged risk of belaboring this point, it occurs to me that any approach to historical wargaming, the blocks and stickers used in Commands & Colors Ancients, for example, homemade unit counters, or a large collection of painted and based 15 mm figures, requires a suspension of disbelief.

Shifting my focus more directly to the scenario that was played, I thought it was realistic (or at least evidence for the argument made by Polybius) that the deployed Roman and Allied legions were not able to stand up to the Seleucid phalangites on open and flat ground. (It was more disappointing than realistic, I think, to see how poor were the pila volleys of the engaged legionaries.) Expanding the perspective a little, it seems realistic that when one side has a pretty substantial advantage in numbers, that side will often emerge victorious. On the other side of this realism “coin,” it bothered me a little that nobody got tired during the battle. The various Seleucid phalanxes and their supporting elephants seemed to approach each new contest and each turn of a prolonged melee as if they were all fresh as daisies. The same assessment can be made for the outnumbered legionaries, the Roman and Italian cavalry, and the Pergamene peltasts. A related question or concern about melees involved the division of close combat into distinct melee areas, wherein a portion of a unit would be involved against a portion or even all the fighting strength of an enemy unit/formation. Understanding that our hobby requires certain levels of abstraction, especially when it comes to resolving life-and-death struggle between two opposing formations of heavy infantry, for example, I sometimes struggle with the procedures provided in rulesets about how to determine who is winning and who is losing. If only a part of the physical unit (or representation of a unit) is in physical contact with an enemy formation, then what percent of its strength or combat value should be counted? Then again, referencing my previous preference for simplicity (and maybe some chrome), it would be easier just to count the opposing units as “fighting” regardless of how much or little of the model unit is in physical contact with the enemy. I wondered, too, about the lack of leadership in my expanded version of Magnesia. As stated, there were historical personalities on the tabletop, but none of these participated in the fighting. The “divisional leaders” required by the rules are essentially “markers,” instead of actual officers with variable abilities and subject to the vagaries of fate. Granted, giving local leaders a greater role would probably complicate things, but the trade off is that another layer of color is added to the battle being wargamed.

Looking back through the electronic document in progress early on this weekday morning in the middle of May (the sun is about an hour from appearing on the horizon), I see that I have typed around 3,000 words in this subsection of what will become my 37th post. That means that roughly one-third of this battle report is dedicated to post-game “analysis,” assessment, and reflection. On further review, perhaps I could limit myself to two paragraphs or even just a few sentences. Maybe I should just ask and answer this simple question: Did I have fun? This “bare bones” approach would certainly save both myself and potential readers a lot of time.

29 Photos taken over 8 Turns

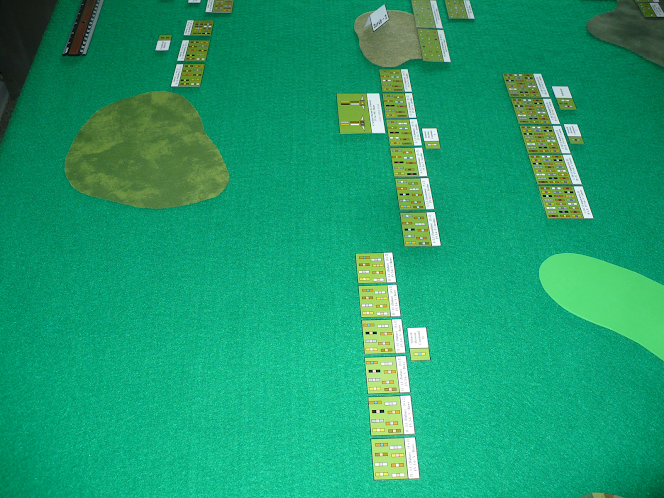

Instead of dropping or mixing the photographs of my game into the body of the narrative, I thought I would try something different with this post. Below, please find 29 pictures which will hopefully capture the back-and-forth and then one-sided nature of the battle as my “miniature” Romans and Seleucids engaged on a model field bearing a slight resemblance to the historical terrain of Magnesia.

Picture 1 / Showing the far left wing of the Seleucid deployment, with the Dahae horse archers very near the banks of the unnamed river (just left of frame) and the Tarentine and Galatian light cavalry to the right. The improvised models of scythed chariots can be seen positioned in front of the Galatian horsemen. A strong contingent of cataphracts is arranged in support on this wing.

Picture 2 / Taken from behind a portion of the Seleucid center, showing two sections of the deployed-in-depth phalanxes. Both formations of pike are interspersed or interrupted with packets of pachyderms as well as protected by light infantry and screened by a variety of skirmishers. The incorrectly spelled command stand for Philippus in plainly visible.

Picture 3 / The Seleucid right wing, showing the large formation of Bedouins on camels, screened by a number of scythed chariots and reinforced by a second command or division of cataphracts.

Picture 4 / On the other side of the field . . . This photo shows the “strength” of the Roman right wing. In addition to the Pergamene heavy cavalry, there is one unit of Roman cavalry and two units of Numidian light horse.

Picture 5 / To the left of the Pergamene lancers (heavy cavalry), there is a decent line of peltasts supported by a small troop of African elephants. There is also a reserve of elephants behind this wing, though the size and numbers of these animals pales in comparison to the elephants brought to battle by Antiochus.

Picture 6 / A view of the legions (Roman and Allied) taken from the right side looking left. The Velites form a screen and this “cloud” is supported by three lines of heavy infantry. The purple markers placed on 2 of the 3 legionary stands represent the pila volley capability.

Picture 7 / The Roman left wing . . . composed of Italian cavalry, Achaean peltasts, a handful of elephants, and in the upper right of the frame, Italian foot and a few skirmishers. The River Frigidarius is visible and the bare steep hill between the opposing lines is obvious.

Picture 8 / A close up of the center of the Seleucid center. Here, the more capable phalangites are shown. The skirmisher screen is visible and the peltasts on the left are partially visible. A troop of elephants is “sandwiched” between the deeply deployed pikemen. (Note: The circles within the ranks and files of squares indicate when the unit reaches its breaking point.)

Picture 9 / A close up of the center-left of the Seleucid deployment. Tons of skirmishers can be seen. The first line or screen covers a large number of Indian elephants. The second line or screen protects an ad hoc group of Galatians and Asiatic mercenaries.

Picture 10 / A close up from behind the center-left of the Roman deployment. Again, the Velites screen the Hastati, the first line of heavy infantry in the legion who carry pila. (The purple marker indicates the one-time ability to use this pre-melee weapon.) The Principes wait to relieve the Hastati, if necessary. These veterans are also armed with pila. The “last best hope” of the legion are the Triarii. These veterans are smaller in number and carry long spears instead of pila.

Picture 11 / The Seleucid light cavalry on their left wing faced nothing but open ground as the Roman numbers and deployment were not sufficient to match those of King Antiochus. Seleucus pushed the cataphracts forward as fast as they could trot. He wanted to get his light and heavy cavalry well behind the right-rear of the Roman position.

Picture 12 / The Pergamene light infantry and Seleucid skirmishers have entered into missile range and are flinging javelins, slinging stones, and shooting arrows. The red markers track unit losses. The green squares with “missile halt” typed on them indicate units that have taken a few hits and failed a required morale or control test.

Picture 13 / In the center of the field, the Velites and their counterparts are playing a deadly game of catch. The temple ruins are being contested by skirmishers of both sides. Although the engagement has just started, it seems that the Seleucid skirmishers are proving their worth against the Velites. Given the proximity of heavy infantry formations, the skirmish exchange cannot last much longer.

Picture 14 / The Arab camel troops have run hot and cold with regard to their arrow volleys. They started off well enough by inflicting a “missile halt” on a unit of Italian cavalry. However, when additional units of Italian riders advanced, the bowmen riding bumps could not find the range. The screen of scythed chariots attacked an enemy formation of peltasts and elephants. Per the rules, there was no impetus to be had and the enemy javelins made short work of the terrified horses as well as drivers who remained in the vehicle. The spinning blades and dying animals did some damage to the Achaeans, but the panicked survivors disordered the supporting camel units in their chaotic flight.

Picture 15 / An overview of the center of the field(table) at the mid-point of Turn 4, taken from behind the Roman main line. There has been an exchange of missiles between the opposing lines or clouds of skirmishers. The Velites have taken quite a few more casualties as evidenced by the bright green “Missile Halt” markers. The supporting lines of heavy infantry, pikemen in deep formations and legionaries in 2-line formations but with 2nd and 3rd line reinforcements, are getting ready to do battle.

Picture 16 / A snapshot of the developing action over on the Roman left wing, where the Italian cavalry have been engaged by the Seleucid camel formations. The Arab archery was hit and miss here, but two successes can be seen with the “Missile Halt” indicators. The scythed chariots are no longer in the picture. The resulting disorder caused to the supporting camel units being resolved, the rest of the Arabs will move into contact with the light infantry the following turn. A strong division of cataphract cavalry can be seen at the right top of the frame.

Picture 17 / Over on the Roman right flank, the Dahae horse archers continue to advance against no opposition at all. Meanwhile, the Tarentines, Galatians, and scythed chariots have engaged the Numidians and one unit of Roman horse. The scythed chariots had momentum and made “horse burgers” of one unit of Numidians. The pursuit move brought these deadly wheeled vehicles into contact with another unit of Numidians who had been justifiably shaken at the slaughter of their comrades. Another strong contingent of Seleucid cataphracts can be seen in the upper right of this frame. These armored horsemen are, of course, slower moving than the Galatians and Tarentines.

Picture 18 / The Seleucid near-left versus the Roman near-right. After harassing the Pergamene peltasts with a variety of missiles, the Seleucid skirmishers withdrew and the line of elephants took over, traipsing into the light infantry. Even though the pachyderms could not claim impetus against the peltasts, their melee dice were much better and holes soon began to appear in the Roman line. In the African vs Indian elephant combat, things were even, at least for now. The Romans were moving up their reserve of African elephants to try and plug the gaps that were appearing in this sector of the battlefield.

Picture 19 / Initial contact has been made between the legionaries and the phalangites in the center of the field/table. Poor dice saw the several volleys of pila have little effect on the deep formations of pikemen. Having to divide their melee dice between two and three enemy formations also lessened the effect of the Hastati, their flexibility and short swords. The Seleucid elephants were slow; only one of the three troops gained the impetus advantage. (See the marker behind the elephant stand/counter on the upper left of frame.) Generally speaking, the combined effects of multiple ranks of pikemen and numerous elephants attacking and trumpeting saw quite a few legionaries from the first line littering the ground.

Picture 20 / The Roman right flank, after the demise of the Numidian light cavalry versus the squadron of scythed chariots. At the top left of the frame, one can just see the retreating Pergamene heavy horse. Eumenes is moving them to a different location. The wounded Roman cavalry unit is facing impossible numbers, but may be able to break off and run away. At the bottom of the frame, the division of Dahae horse archers is visible. After advancing against “thin air,” they have wheeled to the right and are preparing to move against the Roman rear.

Picture 21 / A better view of the withdrawing Pergamene heavy cavalry, but this photo shows the demise of the Pergamene peltasts against a heavy line (pun intended) of Seleucid elephants. The attack of the Roman reserve pachyderms is a last gasp effort and won’t prevent six “models” of the Seleucid nellies from moving against the near right of the Roman legionary line.

Picture 22 / Taken from behind the Roman center, showing the ongoing action in this part of the battlefield. The Romans had the move option or initiative for Turn 6. They also won the melee direction. On the left of this sector, Hastati and Silver Shields have engaged around the temple ruins. Once again, the Roman pila volleys were ineffective. The Roman center is holding, but the Hastati are not faring well against such numbers. On the right of the frame, the absence of Hastati is evident, which resulted in a pursuit by one of the phalanxes and its “attached” troop of elephants. Can the Principes hold or turn the tide? Can they do this before the Seleucid left wing cavalry arrives in strength to make the Roman position untenable?

Picture 23 / A close up of the victorious phalanx and elephants pursuing the Hastati into the waiting ranks of the Principes in this particular sector of the field. (One can only hope the Principes will throw their pila with more accuracy than the first line!)

Picture 24 / Another angle of the contest between the Silver Shields and the Hastati on the Roman center-left. This melee or these melees are taking place on a gentle hill in and around some temple ruins.

Picture 25 / The Seleucid right sans Arabs and camels. The Romans fought well here, but the Italian cavalry are damaged and the weakened peltasts really cannot hope to stand up to a cataphract charge on level ground. Perhaps the small group of African elephants will occupy the cataphracts for a while?

Picture 26 / The Roman right wing after the destruction of the sole unit of Roman cavalry by a formation of Seleucid cataphracts. The pursuit of the “redeploying” Pergamene heavy horse is somewhat disorganized as there are a lot of units trying to move through a limited space. This sweeping move (the Dahae horse archers are out of frame on the lower right of the picture) is being joined by a line of elephants and an untouched command of various troops which has not seen any action.

Picture 27 / A shot of the Roman near right, under heavy pressure from the poorer quality phalangites and the integrated elephants. The Principes are facing superior numbers and there is the concern of no right wing protection, as referenced in the previous caption. The longer the Principes stay and fight, the better the chances that they and the final line of Triarii will be swamped by Seleucids attacking the exposed Roman right and right-rear.

Picture 28 / An overview of the center of the field as seen from the Seleucid point of view. Two of the deep phalanxes have been disordered by some panicked elephants, these animals having been dispatched by a stubborn unit of Principes. This local success is just one bright spot in a rather dark picture or outlook for the Roman line of battle. The Hastati were thrown back and the Principes are under quite a bit of pressure. On the right of the frame, the Silver Shields appear to have control of the temple ruins and the hill on which these sit. On the left of the frame, the lesser phalanx formations are doing well against their Roman counterparts. Given the state of the Roman right, it seems that the Triarii would be sacrificed if they were committed in the center. It also appears that it would be rather difficult to shift them over to the right to create a new line. This move presumes that what is left of the Principes would be able to hold.

Picture 29 / Showing the status of the Roman left/Seleucid right when the battle/wargame was called after 8 turns of play. The cataphracts have contacted the Italian levy foot and have secured impetus for the initial round of melee. King Antiochus is directly supervising the advance of his elite cavalry formations as they move to counter the damaged units of Italian heavy cavalry. The Italians are not in good shape. One unit collapsed very shortly after being engaged by some cataphracts. The routing survivors caused disorder markers to be placed on two friendly formations. Based on numbers involved, quality of troop types, and condition of the Italian/Roman units, it seems fair to predict a Seleucid victory in this sector if the tabletop contest were to be extended for 2 or 3 more turns.

Detailed Orders of Battle

For those readers interested in numbers, point values and the weapons carried by various units, here are the orders of battle for the opposing armies.

Roman Left Flank

Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus (value: 15 figures)

Italian Cavalry (HC x 4 @ 12) FV 4-6, V, Spears / 240 points

Achaean Peltasts (LI x 2 @ 18) FV 4-6, V, Javelins / 252 points

Elephants (2 models - African [impetus]) FV 5-6, V, Various / 60 points

Italians (FT x 3 @ 36), FV 4-6, MG, Various / 540 points

Trallians (SI x 1 @ 10), Sk FV 4-6, V, Slings / 30 points

Cretans (SI x 1 @ 10), Sk FV 4-6, V, Bows / 30 points

Total Points: 1,152 / Total Massed Figures: 200 / Breakpoint: 100

Roman Center-Left

Marcus Aemilius Lepidus (value: 10 figures)

Allied Legion 1:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, EL, Spears / 96 points

Roman Legion IV:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, EL, Spears / 96 points

Allied Legion 2:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, EL, Spears / 96 points

Roman Legion V:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, EL, Pila & Swords / 216 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, EL, Pila & Swords / 216 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, EL, Spears / 96 points

Total Points: 2,160 / Total Massed Figures: 240 / Breakpoint: 120

Roman Center-Right

Lucius Cornelius Scipio (value: 20 figures)

Allied Legion 3:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, EL, Spears / 96 points

Roman Legion VI:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, EL, Pila & Swords / 216 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, EL, Pila & Swords / 216 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, EL, Spears / 96 points

Allied Legion 4:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, MG, Pila & Swords / 144 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, MG, Pila & Swords / 144 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, V, Spears / 84 points

Roman Legion VII:

Velites (SI x 24) Sk FV 5-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Hastati (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Principes (FT x 24) FV 5-6, V, Pila & Swords / 192 points

Triarii (FT x 12) FV 5-6, EL, Spears / 96 points

Total Points: 2,052 / Total Massed Figures: 240 / Breakpoint: 120

Roman Right

Eumenes of Pergamon (value: 15 figures)

Elephants (3 models - African [impetus]) FV 5-6, V, Various / 90 points

Pergamene Peltasts (LI x 6 @ 12) FV 4-6, V, Javelins / 504 points

Elephants (2 models - African [impetus]) FV 5-6, V, Various / 60 points

Pergamene Cavalry (HC [impetus] x 2 @ 16) FV 5-6, V, Lances / 256 points

Roman Cavalry (HC x 1 @ 12) FV 4-6, V, Javelins / 72 points

Numidian Cavalry (LC x 2 @ 10) FV 3-6, V, Javelins / 80 points

Total Points: 1,062 / Total Massed Figures: 156 / Breakpoint: 78

Seleucid Far Left

Seleucus (value: 12 figures)

Dahae (LC x 6 @ 8) FV 3-6, V, Bows / 240 points

Cataphracts (HC x 5 @ 24), FV 5-6, V, Lances / 960 points

Tarentines (LC x 2 @ 10) FV 3-6, V, Javelins / 80 points

Galatians (LC x 4 @ 10) FV 3-6, V, Javelins / 160 points

Scythed Chariots (3 models of 4-horse chariots [impetus]) FV 5-6, MG, Blades / 81 points

Total Points: 1,521 / Total Massed Figures: 240 / Breakpoint: 120

Seleucid Near Left

Peltasts (LI x 1 @ 12) FV 4-6, MG, Javelins / 36 points

Peltasts (LI x 1 @ 24) FV 4-6, MG, Javelins / 72 points

Galatians (WB x 2 @ 40 [impetus]) FV 4-6, V, Spears & Swords / 520 points

Asiatics (FT x 2 @ 30) FV 3-6, MG, Various / 180 points

Scythed Chariots (2 models of 4-horse chariots [impetus]) FV 5-6, MG, Blades / 54 points

Skirmishers (SI x 3 @ 24) Sk FV 4-6, V, Bows, Slings, or Javelins / 216 points

Peltasts (LI x 1 @ 12) FV 4-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Peltasts (LI x 1 @ 24) FV 4-6, MG, Javelins / 72 points

Elephants (3 units of 4 models - Indian [impetus]) FV 5-6, V, Various / 504 points

Elephants (1 units of 2 models - Indian [impetus]) FV 5-6, V, Various / 84 points

Skirmishers (SI x 7 @ 24) Sk FV 4-6, V, Bows, Slings, or Javelins / 504 points

Total Points: 2,290 / Total Massed Figures: 304 / Breakpoint: 152

Seleucid Center

Philippus (value: 20 figures)

Peltasts (LI x 1 @ 12) FV 4-6, MG, Javelins / 36 points

Elephants (2 units of 2 models - Indian [impetus]) FV 5-6, V, Various / 168 points

Settler Phalanx (PH x 6 @ 60) FV 4-6, MG, Pikes /2,160 points

Skirmishers (SI x 2 @ 24) Sk FV 4-6, V, Bows, Slings, or Javelins / 144 points

Peltasts (LI x 1 @ 12) FV 4-6, V, Javelins / 48 points

Elephants (1 units of 2 models - Indian [impetus]) FV 5-6, V, Various / 84 points

Phalanx (PH x 4 @ 60) FV 4-6, V, Pikes /1,680 points

Skirmishers (SI x 3 @ 24) Sk FV 4-6, V, Bows, Slings, or Javelins / 216 points

Peltasts (LI x 1 @ 24) FV 4-6, V, Javelins / 96 points

Argyraspides / Silver Shields (PH x 4 @ 48) FV 5-6, EL, Pikes /1,536 points

Skirmishers (SI x 3 @ 24) Sk FV 4-6, V, Bows, Slings, or Javelins / 216 points

Agema (HC x 1 @ 18) FV 5-6, EL, Lances / 162 points

King Antiochus III “The Great” (value: 30 figures)

Companions (HC x 2 @ 18) FV 5-6, EL, Lances / 324 points

Agema (HC x 1 @ 18) FV 5-6, EL, Lances / 162 points

Total Points: 7,032 / Total Massed Figures: 948 / Breakpoint: 474

Seleucid Right

Scythed Chariots (5 models of 4-horse chariots [impetus]) FV 5-6, MG, Blades / 135 points

Arabs (CM x 5 @ 18) FV 4-6, MG, Bows & Various / 630 points

Cataphracts (HC x 5 @ 24), FV 5-6, V, Lances / 960 points

Total Points: 1,725 / Total Massed Figures: 230 / Breakpoint: 115

Notes

- Searching through the Index of Slingshot, The Journal of the Society of Ancients, I found a handful of articles. See, for example, “Magnesia Refought [ with amended WRG 6th],” by S. J. Randles in Issues 114, 115, and 117. Issue 171 saw the publication of “Magnesia Refought [with PHALANX],” by Philip Sabin, as well as “DBM in Hong Kong [Magnesia refought],” by Bruce Meyer. Mark Grindlay covered the Armati perspective in Issue 265 with a four-page piece entitled “Magnesia.” In Issue 278, Dr. Chris Winter offered the FOG point-of-view with “Refighting Magnesia: A large multi-player game using Field of Glory.” Searches of the Internet turned up some additional efforts. I read, with interest, Luke Ueda-Sarson’s DBM Scenario for Magnesia. It would be fair to admit that I almost drooled over the posts made by Simon Miller regarding his experience with the historical battle. See, for example, the spectacular November 6, 2016, entry made for “Magnesia at Crisis.” Over on the Tactica II Forum, I was kindly directed to the Files section wherein I found, downloaded, printed, read and annotated, Bob Burke’s scenario for refighting Magnesia.

- I have often referenced the bottom of page 10 of Donald Featherstone’s Battle Notes for Wargamers, where this “founding father” of the hobby codified the following common sense advice: “To refight any historical battle realistically, the terrain must closely resemble both in scale and appearance the area over which the original conflict raged, and the troops accurately represent the original forces.”

- To be certain, the goal was not a museum-quality masterpiece. I was aiming for something like a decent looking bowl of fruit or pastoral scene as opposed to something that resembled the finger painting efforts of a 6-year-old who had just eaten three chocolate bars.

- Simon Miller, a rather well known name in the hobby, was generous enough to take time out of his busy schedule and email me advice as well as a brief containing orders of battles, a deployment diagram, and historical source materials. My attempt to stage something like Magnesia using his rules and updates collapsed, for a variety of reasons, at around Turn 4. The period of “mourning” after dismantling this attempt was filled with a number of attempts to start a new draft. Each of these sputtered to a frustrating halt after 1,200 words or so. Thinking I finally had Magnesia managed, I set about with some new ideas about how I might stage an even larger contest using modified ADLG (L’Art de la Guerre) rules. One of the focal points of this attempt or experiment was how my model of a Republican (Polybian) Roman legion would fare on the tabletop. Once again, unfortunately, at around Turn 4, coincidentally, the “wheels came off” of this sizeable solo wargame. Needless to say, I was disappointed, discouraged, and perhaps a little depressed. I briefly considered taking up a new hobby, such as bird watching or learning how to play the banjo.

- Please see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Size_of_the_Roman_army or https://www.unrv.com/military/roman-republican-legion.php. There are, of course, more than two websites covering this topic. Readers might also find it worth their time to check out a number of YouTube videos on the Polybian or Manipular Legion.

- Interested in finding out about the frontage held by a Roman legion during this time period, I conducted a Google search. A possible lead was found at https://www.jstor.org/stable/24432811. According to the abstract, “In five set-piece engagements, Roman legions presented fronts of between 320 and 570 meters.” Interestingly, it is suggested “that modest inter-manipular gaps were maintained even as the heavy infantry lines clashed.” Anyway. Using the provided estimates, it appears that my eight “model” legions would present a frontage of between 2,560 and 4,560 meters (between 1.6 and 2.85 miles). On a related concern or note, in my previous attempts, I wrestled with depicting the three or four line formation of the Republican or Polybian legion. Researching this often discussed (or debated) issue, I was grateful to find a couple of articles in an old Slingshot that I was able to apply or at least reference. Coincidentally, both were published in Issue 278 (September 2011). The eminent Richard Taylor penned “Files, Gaps and Maniples,” while a Dr. Chris Winter was the author of “The Missing Lines: Where are all the Triplex Acies on our gaming tables?” I suppose, for the sake of being thorough, I should also include “Holes in the Checkerboard: A Fresh Look at Line Relief,” written by Justin Swanton and published in the March-April 2016 issue of Slingshot.

- Careful readers will note that I have not included the Roman camp guards, a garrison of, reportedly, 2,000 Macedonians and Thracians. If I did decide to employ the camp guards, I would need 80 “figures.”

- Evidently, the Seleucids drew up their phalanx 32 ranks deep. See the bottom of page 198 in Professor Sabin’s LOST BATTLES. Typically, phalanxes are just 4-ranks deep in Tactica II games. Typically, units with multiple ranks benefit from a “depth bonus,” which translates in extra combat dice.

- The following excerpt is taken from Dr. Winter’s “Refighting Magnesia” article in the September 2011 issue (Number 278) of Slingshot. As formatting this excerpt has proven rather problematic, I have decided to change the color of the font as well as put it in italics, so that readers can easily determine the start and end point of the selected passage. When we compare various gaming periods one stark feature that emerges is that most ancient period games have less terrain than other periods. Why, I am unclear. A typical battlefield will consist of a couple of smallish hills, perhaps a wood or two and a village. Magnesia was one of the great clashes between phalanx and legion. In explaining why the unstoppable phalanx does not win Polybius cites the fact that no real battlefield is flat but is cut with “ditches, gullies, depressions, ridges and watercourses” all of which disorder the steamroller of the phalanx. If we look at most of our gaming tables no such real world features intrude on the billiard table. Apart from a river on one flank ancient authors make no mention of terrain at Magnesia. I suspect this is because small features are taken for granted and only strategically significant terrain is thought worth reporting in the short reports we have of most battles. And what winning general wants to credit the terrain as helping deliver his victory? The actual tabletop layout was thus created in the spirit of Polybius, with low ridges, a shallow depression, areas of rough ground and brush and with both camps on slightly elevated ground. More small features were present than the rules would allow in a random set up.

- Please see https://www.thewargamespot.com/magnesia-190bc-super-field-of-glory-aar/.

- The Terrain Effects Chart on page 53 of the Tactica II rulebook contains the following terrain types: Open Ground, Gentle Rise, Steep Hill, Woods, Rough Ground, and Streams. On page 65 of the ADLG rulebook, a Terrain Table lists the following types: River, Coastal Zone, Hill, Steep Hill, Brush, Field, Plantation, Wood, Marsh, Sand Dune, Gully, Road, Village, and Impassable. Chapter 3.0 of the IMPETVS rules covers Terrain and Deployment. Following a statement about how “battles were rarely fought on a wide plain without slopes, rivers, towns or woods,” this section identifies half-a-dozen types of terrain for movement, missile, and melee purposes. These 6 terrain types are: Open ground, Broken ground, Difficult ground, Impassable ground, Roads, and Rivers.

- Please see the information provided in Note 6.

- In Issue 117 of Slingshot, S. J. Randles explained: In fact in the end I refought Magnesia three times. The first game was played using historical tactics and dispositions; the second was a repeat of the first, except that the Seleucid chariots and camels were omitted from the deployment; the third was played with the Seleucids using traditional Hellenistic deployment and tactics.

- I also find myself drawn to the orders of battles and ideas or game notes provided by Roger Cooper on the TRIUMPH! Forum. (Please see https://forum.wgcwar.com/.) He establishes a unit scale of 1,000 for each infantry formation and 500 for each cavalry formation. The Romans will have 41 units available, while the Seleucids will bring 53 to the table. I am tempted!