CHAERONEA:

REVISITED & REVISED

Frustrated by numerous attempts to draft a coherent, engaging, and interesting narrative about a recently completed solo wargame wherein a large army led by Hannibal Barca faced off against an equally large army commanded by Pyrrhus of Epirus, I decided to take a day or two off and then return “once more unto the breach,” if the appreciated reader will permit me to use a phrase from Shakespeare’s Henry V. [1] Instead of returning to the disconcertingly vexing analysis and exploration of that—appealing as it was—particular counterfactual, I embarked upon another.

In August, I read James Romm’s excellent new book, THE SACRED BAND - Three Hundred Theban Lovers Fighting to Save Greek Freedom. (For those readers who may be curious about the text, please see https://www.simonandschuster.com/books/The-Sacred-Band/James-Romm/9781501198014.) Professor Romm notes that while the Sacred Band fought on the left of the line of battle at Leuctra (371 BC) and at Mantinea (the second one, fought in 362 BC), it was deployed on the right of the line at Chaeronea (338 BC). The elite corps of 300 men, made up of 150 pairs of lovers, was destroyed by the Macedonian father and son team of Philip and Alexander. In his brief summary of Chaeronea, Professor Romm wonders what might have happened if the Thebans and their well known Sacred Band had been stationed on the left of the Allied Greek line. Needing no more inspiration than this intriguing suggestion, I secured my well-worn copy of Warfare in the Classical World and turned to pages 68 and 69, where I found the familiar as well as wargamer-friendly diagrams, orders of battle, and chronological summary of the historical engagement. [2]

Rules and Orders of Battle

Curious to see how or even if the recently acquired TRIUMPH! rules could handle this historical battle, I opened up the PDF and started refreshing my memory and reviewing key aspects of the rules. [3] I also studied the “rough draft” version of GRAND TRIUMPH!, as there appeared to be approximatley 65,000 men on this ancient battlefield.

Looking over the Greek Allies order of battle, it appeared that I could establish or use an approximate unit scale of 1:1000. This would give me, according to the information provided in Warfare, 10 units of Athenians, 8 units of various allied city-state contingents, and 12 units of Thebans. There would be 5 additional units, divided into 3 of peltasts and 2 of psiloi. Studying the Later Hoplite Athens as well as Later Hoplite Theban/Boiotian [sic] army lists found on MeshWesh (please see http://meshwesh.wgcwar.com/home), I figured that 10 units of Athenian hoplites (heavy foot) along with 2 units of peltasts (light foot) and 1 of psiloi (rabble) would add up to 38 points, which is exactly 10 points shy of the typical size of a regular army for a basic friendly or competitive game of TRIUMPH! The allied contingents would add up to 24 points of heavy foot, while the Theban contingent would number 42 points worth of elite foot (the Sacred Band), heavy foot, light foot, and rabble. Added together, the Greek Alliance would have 104 points on the table.

Employing a similar yet very approximate unit scale for the Macedonian army, I prepared 3 units of Hypaspists (raiders), 24 units of phalanx (pikes), 2 units of peltasts (light foot), 1 unit of slingers (skirmishers) and 2 units of psiloi (rabble). Turning to the cavalry arm of the invading army, technically, I should have stayed with the same approximate unit scale. However, after thinking it over for a bit, I decided to build 4 units of Companions (knights) and 1 unit of light horse (javelin cavalry). Adding the value of these various units together, I arrived at a sum of 117 points. Given that Philip and Alexander were on the field, I figured that I would divide the Macedonian army in half, roughly speaking. The father would command on the right while his son would take the left. They would share responsibilities in the center.

Looking over the QRS, I noted that the Greek hoplites would have a +4 factor in close combat against enemy foot. Conversely, the “blocks” of Macedonian pikemen would only have a factor of +3 against the hoplites. This advantage did not feel right, at least to me. One solution was providing the pikemen with rear support. This would increase their combat factor to +5. However, the addition of 24 more pike units or stands would increase the value of the Macedonian army by 72 points. Furthermore, if the approximate unit scale was retained, then there would be 24,000 men added to the army of Philip, giving him a substantial advantage. Another solution was to give the pike units the rear support bonus without fabricating the physical second unit required for the rear support bonus. This would eliminate the need to add more points and more men to the army, but it would require me to imagine that the stands of Macedonian pikemen were in fact deployed in depth (something like the option employed in Armati) as opposed to being on equal frontage with the hoplite phalanxes of the Greek Alliance.

Terrain and Deployments

It occurs to me that the nature of the ground at Chaeronea did not have a significant impact on the course of the battle. However, the Acropolis and the marshy patches along the bank of the River Cephissus did serve as “bookends” or boundaries for the Greek Alliance. Taking a minimalist approach as opposed to an expert modeler of terrain approach, I crafted a very rudimentary Acropolis and placed it on top of some elevated ground. A similar process was used to depict the patches of marsh along the river. The rest of my tabletop was designated as flat and open terrain.

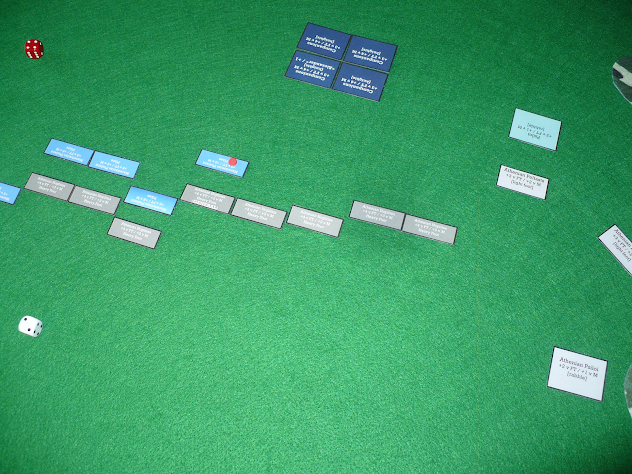

For this abstract-compared-to-other-models reimagining of Chaeronea, the Athenians and Thebans switched places. The Sacred Band would hold the far left of the Allied line; it would be nearest to the Acropolis, but drawn up on level ground. To the right of the Theban formation would be the various Allied contingents. The Athenians would be on the right, with their light troops closest to the marshy ground. Not very far away, the Macedonians were arranged for the coming battle. (In fact, Philip’s forward elements were just 10 MUs or 20 centimeters from the enemy line.) Due to command and control concerns, I did not deploy the pike phalanx in what I will call “complete echelon.” That is to explain, each unit of the phalanx was not positioned as a single step on a 24-step staircase, descending toward to the Macedonian left. After tinkering with the command radius or reach of both Philip and Alexander however, I was able to arrange the Macedonian army in a shallow “staircase formation.” [4] The Hypaspists and light troops were on the extreme right of the line. Then, there were four “steps” of pikemen, each “step” of the phalanx containing 6 units. The rest of the light troops and the single unit of light cavalry was posted to the far left, very close to the river and marshy ground. Alexander, along with the four units of heavy cavalry were positioned between the last block of pikemen and the light troops guarding the Macedonian left.

This photo taken from high above the Macedonian right. A portion of the “model” hill and Acropolis can be seen. The Theban hoplites are represented by the dark red stands; the Sacred Band is represented by the purple stand, and the light troops are in gray. The Macedonians lead with their Hypaspists, protected on the right by some peltasts and psiloi. Part of the “shallow staircase” formation of the phalanx can be seen.

How It Played: A Brief Summary

The first couple of turns were one-sided affairs, as the hoplite phalanxes of the Greek Alliance stood like statues awaiting the approach of Philip’s army. Having arranged his troops in a shallow echelon formation, the Hypaspists and light infantry were twice as close as to the Thebans as the troops under Alexander’s control were to the Athenians. [5] The next several turns saw both sides engaged along most of the line as the “steps” of the Macedonian phalanx advanced the final distance and made contact with various sections of the Greek line. King Philip and his son were plagued by poor command rolls, unfortunately. They were also apparently cursed by the dice gods as their combat rolls left much to be desired. Philip’s Hypaspists found themselves rather roughly handled on the right, while Alexander’s light troops were quickly facing complete annihilation on the left. On either flank, the initial charge of the pike phalanx was repulsed or held. A unit of Athenian hoplites managed to get the better of their antagonists and whittled down a pike block to half its original size. It was only in the center where the Macedonians had success. Oddly enough, the dice gods favored them in this sector, and the various allied contingents soon found themselves in very dire straits. First one hoplite unit fell to the wall of pikes, then another, and then another. The general of this varied force was the next to meet his end along with his desperately fighting men. It seemed that in a matter of minutes several large holes had been torn in the Greek line. Demoralized by this sudden shift, the surviving units of the Greek center fell back and then turned tail to retreat off the field. With the collapse of their center, the Greek position was judged untenable, even though father and son had been frustrated by the Thebans and Athenians. In fact, it could be remarked that both had been given a bloody nose by the stubborn hoplites of each city-state.

Philip’s Hypaspists have engaged the Theban left. They are supported by some peltasts and are facing some light troops, a unit of Theban hoplites, and the Sacred Band. Philip is with the second pike phalanx on the left of the frame. Poor command dice left him unable to commit his pikemen to the fight (at least for this turn) and so, his elite Hypaspists would be overlapped on their left.

On the opposite side of the field, Alexander has his hands full against the Athenians. His peltasts, slingers, and light horse have been routed by their Athenian counterparts.The Athenian hoplites have done rather well against the Macedonian pikemen, too. The young commander thought several times about entering the fray, but given his die rolling ability (a case of nerves?) and given the even factors between knights and heavy foot in frontal combat (each rated at +3), he decided not to charge into battle. (The Macedonian unit with the red marker indicates a pike block that has only one stand instead of two.)

To rearrange the common saying: “Like father like son . . .” to “Like son like father . . .” Over on Philip’s flank, his elite troops were having serious difficulties against the Theban hoplites, Sacred Band, and light troops. Adding insult to injury, Philip’s command dice were pretty consistently terrible, thus hampering his efforts to better control the tempo of the battle in this sector.

Taken over the center of the Greek Alliance position, this photo shows the beginning of the end for this particular contingent. The Macedonian phalanx has ruptured this part of the line in three places, and has pushed back the enemy in at least two more. The dice gods favored the anonymous Macedonian commander in this sector apparently, and frowned on the leader of the allied contingents. In another turn or two, the center would be non-existent. The few surviving hoplite units would be demoralized and routing to the rear.

Reflection

I believe that I am getting more used to the TRIUMPH! rules. To be certain, I am nowhere near being an expert. I am far from achieving the rank of veteran. I needed to check with the more experience players on the TRIUMPH! Forum about a rules question, and I mistakenly allowed the Allied Greek command to keep fighting for a turn when its remaining units should have been marked as demoralized and its free units (those not in combat or contact) should have been routed as well. This error did not tilt the wargame or experiment one way or the other, however. It simply delayed the inevitable: a Macedonian victory.

It appears then, based on the limited evidence of this counterfactual (along with the accepted historical record), that the location of the Theban Sacred Band had no impact whatsoever on the outcome of the contest at Chaeronea. Historically, they fought well, but were surrounded and slaughtered. In my fictional engagement, they also fought well. They made the Hypaspists pay dearly and they gave Philip the fits, for lack of a better word. However, they could not prevent the rupture and destruction of the Greek center, which cost the Alliance the battle/wargame.

I found it interesting, frustrating, and sometimes amusing that both Philip and Alexander were plagued by poor die rolls. Throughout the comparatively short wargame, I kept wondering if I should have tinkered with the command abilities for both personalities. For example, I thought about giving Philip a larger command radius. I thought about adjusting Alexander’s as well. I even toyed with the idea of shortening the reach of the Greek commanders. Given their poor die rolling, I wondered about changing the d6 of Philip and Alexander to a d8 or even a d10. For example, I could easily see Hannibal or Caesar as a d10 commander. Those leaders who were found more toward the incompetent side of the commander rating spectrum might be assigned a d4. Then again, one could also borrow the fairly familiar idea of using 2d6 and taking the better score.

I confess that it is difficult to divorce myself from a representative figure or unit scale. The accepted strength of the Sacred Band is 300 men. If that is the basic unit scale, then the roughly 12,000 Theban hoplites would be depicted with 40 stands or bases or elements. In my very amateur effort of refighting Chaeronea, each Theban stand or unit was approximately 1,000 men strong. The Sacred Band formed about a third of one of these units. There were a couple of other mechanics or processes that I continue to struggle with in the TRIUMPH! rules. One of these was moving obliquely, even though the advancing units were very close to the enemy. (They were not within the ZOC, however.) I also had difficulty with the alignment or “snapping to” in a couple of instances, as it appears that this might result in the non-active player having a portion of his line shift right or left, thus leaving a unit of units exposed to potential overlaps. It seems to me that the burden should be on the attacking player. To reiterate, I am getting better with the rules or feel that I am. It is entirely possible that I am not progressing, and I have much more work to do.

Given the nature of the deployments and the terrain across which this wargame was played, it was a very straightforward contest. Pretending to be - sequentially during part of a turn - one of six identified commanders on the tabletop battlefield, I do not believe I showed any bias to either side or any particular command. I did not try to execute any “gamey” moves. Generally speaking, I simply advanced the Macedonian phalanx into the waiting line of Greek hoplites. If anything, I was perhaps too conservative and thus perhaps not very realistic when portraying Alexander during each turn. The difference between his action during the historical battle and his action during my staged refight was like the difference between night and day.

During the historical battle, Philip was able to draw the Athenians, or a good number of them, out of line, out of position. This feint opened up the Greek line and allowed Alexander the avenue by which he could sweep around the Greek right and fall upon the Thebans. As I had switched the deployment of the Thebans and Athenians, perhaps I should have drafted some scenario rule or “battle card” to inflict the same possibility of the Theban hoplites.

While I was able to fit the entire battle, or my version of it, on my tabletop, I did sometimes find the dimensions of the counters to be a bit fiddly. (I also noticed that my green cloth seems to be “pilling” on the one side. At least I think that is the term. This sometimes interfered with the placement and alignment of the units.)

Overall, I think the TRIUMPH! rules were able to handle Chaeronea. I have seen or read about examples of the rules “tackling” other historical engagements. It might prove entertaining and educational to see how TRIUMPH! does with the contests that have been selected for Battle Day. How would these rules perform when refighting Chalons, Gaugamela, Kadesh, Pharsalus, Poitiers, or Zama?

Hmmm . . . Zama. Now there’s an interesting thought.

SUGGESTED READING/VIEWING

For those with the interest and time, here are a number of links to information about the historical battle:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Chaeronea_(338_BC)

https://www.livius.org/articles/battle/chaeronea-338-bce/

http://www.arsbellica.it/pagine/antica/Cheronea/Cheronea_eng.html

There are also a number of YouTube videos available.

To be sure, Chaeronea has been wargamed many times. Following, please see five sites/blogs reporting on traditional refights of the engagement:

https://www.vislardica.com/vb-sc-chaeronea

http://sparkerswargames.blogspot.com/2015/12/chaeronea-338-bc.html

http://shaun-wargaming-minis.blogspot.com/2014/09/battle-of-chaeronea-338bc-using-ancient.html

https://wargames.richardevers.nl/chaeronea.htm

http://palousewargamingjournal.blogspot.com/2018/08/chaeronea-to-strongest-style.html

Notes

- I feel it necessary to warn readers that the following note is of an unusual perhaps even ridiculous length. In my defense, there is a lot to unpack, as people sometimes remark. I very much appreciate the reader’s patience and perseverance with what follows. This was one of my bigger battles using the Armati 2nd Edition rules. Instead of simply doubling the Core Units, Bonus Units, and Control Ratings, I decided to draft armies six times the usual size and reinforce them with 600 points worth of bonus units. When I was all done with creating the orders of battle and fabricating the various formations, I found that I would be commanding over 225 units on my table. For those readers interested in details, Pyrrhus would have 116 units in his army. Half a dozen of these were veterans. There were 28 cavalry units and 6 elephant units; the rest were infantry. There were 70 ‘key’ units in this grand army; 40 of these were PH (heavy infantry) units with a breakpoint of 4. (The veteran PH units had a breakpoint of 5.) In contrast, there were 111 units in Hannibal’s army, 6 of which were veterans. He had 40 cavalry units (almost half were Numidians) along with 8 units of small elephants as opposed to the larger breed employed by Pyrrhus. There were 89 ‘key’ units in this polyglot yet powerful force. The cavalry arm was the most numerous, followed by 28 foot formations and then a host of 21 warbands filled with screaming, half-naked barbarians sporting tattoos and wild hair. To be certain, my armies and my fictional ancient battlefield looked nothing like the immense and impressive wargames featured in the colorful March 2012 issue of WARGAMES illustrated®. My large tabletop was rather small compared to those used by a collection of accomplished historical wargamers. In fact, my playing area was smaller than the smallest table used in the American Civil War battle/scenario! To be sure, the terrain for these three impressively huge engagements was eye-catching and period appropriate. It certainly added to the atmosphere. (Though I did wonder how much use one would get from a sculpted table measuring 22 feet by 8 feet, and where or how one would store it.) Thousands of figures were used by the groups of enthusiasts. For the ACW scenario alone, there were about six thousand 28mm figures positioned on the various tables. (The mind, or my mind at least, reels at these numbers, at the size of the wargame.) All three games were historical or based in history. My scenario was ahistorical. Finally, these massive projects were collaborative efforts. The player-generals are pictured in two of the narratives, and each battle drew 12 or more historical miniature gamers to the table side or table sides. The intention of my solo wargame project was two-fold. First, I wanted to distract myself from the perennial disappointment of not being able to attend Battle Day. (Please see https://www.soa.org.uk/joomla/battle-day.) Second, I was interested in testing some ideas/rules about command and control, especially when dealing with such large forces. Ideally, my coherent, engaging, and interesting narrative would have utilized as well as seamlessly blended the information from four sources. The first was “Solo Wargaming,” an excellent article authored by admitted non-expert John Hastings which appeared in the July/August 2021 issue of Slingshot, The Journal of The Society of Ancients. The second was found in the same publication, but the author was Anthony Clipsom, and his thought-provoking piece was titled “Game Mechanics and Realism.” The third and fourth sources or “mines of information” were the discussion threads “Are ahistorical match-ups really all that bad?” and “Wargaming vs Historical Tactics,” which received rather a lot of attention on The Society Forum, as one might expect. If the reader will permit me to extend an already gargantuan note, I would like to comment on the first discussion thread and then a make a couple of remarks about the introduction to the article written by John Hastings. With respect to the discussion thread, the phrasing of the question regarding the value of ahistorical match-ups seems rather poor if not prejudiced. Then again, I suppose that most value-oriented questions are. Perhaps something along the lines of “What do members think of ahistorical match-ups?”would have been less judgmental or leading. Turning, finally, to the introduction of John’s article (my guess is that it was penned by the editor, but I cannot be absolutely sure), I wonder what evidence there is to back up the claim regarding the “scattered nature of the Ancients wargaming community”? I wonder too, if this is a condition limited to just wargamers interested in the time span 3000 BC to 1500 AD. I cannot help but be curious; do Naval, ACW, and First Carlist War enthusiasts live next door to one another or on the same block? The use of the term schizophrenia when describing solo wargamers gave me pause. As a veteran solo wargamer, I am offended if not insulted. It seems that a more positive, less diagnostic approach could have been taken here. What about admiring or applauding the strength or perseverance of solo wargamers? These individuals have to do twice the work of a “normal” player-general. Was the use of this term meant in jest? Is the author of this introduction a medical professional with years of experience? I wish that he would have taken a few minutes to check on the definition of schizophrenia before putting words to the page. According to the website https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/schizophrenia/what-is-schizophrenia, accessed on August 20, 2021, “Schizophrenia is a chronic brain disorder that affects less than one percent of the U.S. population. When schizophrenia is active, symptoms can include delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, trouble with thinking and lack of motivation.” Furthermore, “The complexity of schizophrenia may help explain why there are misconceptions about the disease. Schizophrenia does not mean split personality or multiple-personality.” To reiterate, speaking (well, typing) as a solo wargamer with quite a few years of experience in addition to a fairly decent record of publication, I take offense at this potentially libelous statement. Given the above definition, how could I set up a wargame after wargame, play them, and prepare narratives of the action for publication or posting to a blog if I had “trouble with thinking and lacked the motivation”? If it was in fact meant as a joke, then in my opinion, it was a very poor one.

- I relied upon Warfare in the Classical World as well as other sources when I refought Chaeronea with ADLG (L’Art de la Guerre). Please see “Another Consideration of Chaeronea” in the July/August 2016 issue of Slingshot.

- I admit that there is a degree of irony in this selection. In a recent post titled “TINKERING WITH TRIUMPH!,” I explained that I had some difficulties getting used to the system and its mechanics having played with other sets of rules for decades. One “sticking area or point” for me especially was not tracking, in some fashion, the degraded status of a unit as it moved and fought. In the recently completed Hannibal versus Pyrrhus contest, I found myself growing tired of marking scores of units with casualty markers, fatigue markers, and disordered or un-formed markers. Given the number of units on my tabletop, near the end of the wargame, the battlefield looked like a city street filled with bits of confetti after a parade had passed.

- The standard reach or range of a commander is 16 MUs (32 cm, 48 cm, or 64 cm, depending on frontage of the units selected for play). Initially, I toyed with the idea of “limiting” the Greek commanders to 15 MU or perhaps even less. The sub-general responsible for the Allied Contingent of the Greek Army did not need 16 MU of command radius. I also toyed with giving King Philip a command reach of 20 MU or even 24 MU. His son was rated at 16 MU to start and then his ability was increased so that he could share command with “dear old dad.” However and unfortunately, I was unable to decide upon a sufficient spilt with respect to command. Consequently, I created a sub-general to command the central “steps” of the phalanx. The Macedonians would also have three armies or commands then, just like their Greek Alliance enemies.

- Even though my effort was essentially a map exercise played with miniature wargaming rules, I had no trouble picturing the steady, impressive, and I would imagine quite frightening advance of the Macedonian pike phalanxes. I wondered if they sang or chanted, or did they advance in relative silence, except for the commands spoken by file leaders and the like. Conversely, I wondered what the Macedonian infantrymen, at least those in the first few ranks, might feel and think as they approach a solid line of very quiet Greek hoplites. To be sure, the visual spectacle of painted and based miniatures was lacking, but so was the sight of bent and or warped sarissas. There was also no fear of impaling a finger or palm on a pike block or hoplite phalanx. Additionally, there was no worry about inflicting dice damage on purchased, painted, and prepared-for-battle 15mm figures.